Many maths teachers will be excited by news of A-level maths entries in England crossing the 100,000 entries mark this summer. Indeed, this development echoes a recent report by Axiom Maths which said England was more a nation of “shy mathematicians” than one of “anti-mathematicians.”

So, what is making this subject and its near cousin, Further Mathematics, so popular, contrary to the common rhetoric and allegedly popular badge of honour of being ‘bad at maths’?

In searching for answers, we firstly need to discount it being about the numbers taking Maths GCSE. The number of students taking the Higher tier for GCSE Maths has remained stable between 41% and 43%. It is also not because of any increase in the number of students taking extra maths qualifications such as AQA’s Level 2 Certificate in Further Maths.

Neither is it simply the result of a population increase of 15 to 19-year-olds in England, as that has been projected to be less than a 2% increase between 2023 and 2024, and also because if this was the driver, one would have expected to see similar increases in other subjects.

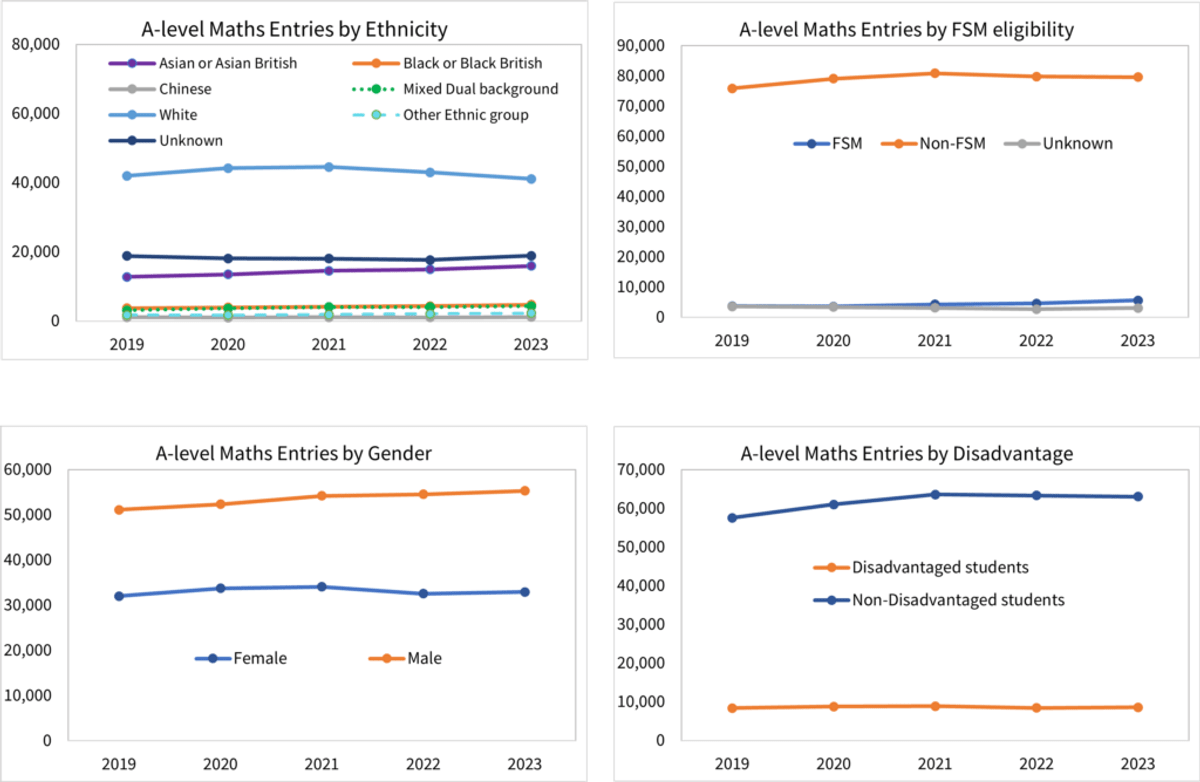

Are there different demographics taking the A-level Maths exam than previously? Well, gender, FSM eligibility, disadvantage and ethnicity distributions across the subject haven’t changed significantly as shown below. But the picture may be different once those for the 2024 entries become available.

Data Source: Ofqual

So, none of these factors yet explain the phenomenal 11.4% increase in A-level Maths’ entries from 90,845 to 101,230 entries from last year to this, which is no mean feat given the meagre 1.4% increase in the number of entries from 2022 to 2023 and even less so in prior years.

Let’s look at another angle. Students who were entered for A-level Maths and Further Maths this year took their GCSE Maths in 2022 and had additional support, including some exam content provided, as part of the government’s package “to provide a safety net for students” due to the coronavirus pandemic.

That year, 30.6% of students got a grade 6 and above compared with 24.9% and 27.2% in the years before and after, respectively, according to JCQ. Could this have boosted their confidence in taking A-level Maths and Further Maths, which also saw a 19.8% increase in entries between 2023 and 2024?

It will therefore be interesting to see what the performance of this cohort is when the results come out next week, especially as this is the first cohort of students to have seen a return to pre-pandemic summative assessments having had their learning disrupted in years 9 and 10.

Another explanation for the significant rise in the uptake of A-level Maths, slightly behind the 11.8% and 12.6% increase in one year for A-level Computing and Physics entries respectively, could be the IT skills shortage. With the International Data Corporation predicting that “90% of organisations worldwide will feel the pain of the IT skills crisis,” could young people be actively re-assessing their choice of qualifications to align with the needs of the job market?

Pieces such as this BBC article on the “UK tech talent shortage” and the reported over two million UK job vacancies in tech the year before may have increased the popularity of maths interventions such as Maths Circles and may have had some effect on students if they perceive it as giving them better scope for a job, if not a high paying one, in future. And if a new graduate can earn as much as £50,000 as a software developer, what’s not to love? Computing entries also grew by 66% in the last five years.

Whatever the case, it is encouraging to see that the reputation of being good at Maths is taking the path of no longer being something to be shy about. Long may it last!