© iStock.com/srdJanPav

The OECD has said women are an “untapped source of digital innovation”. A Women in Tech report has similarly highlighted that 90% of people believe the technology sector would benefit from a “more gender equal workforce.” Are there signs this will get better in the future?

The short answer is no.

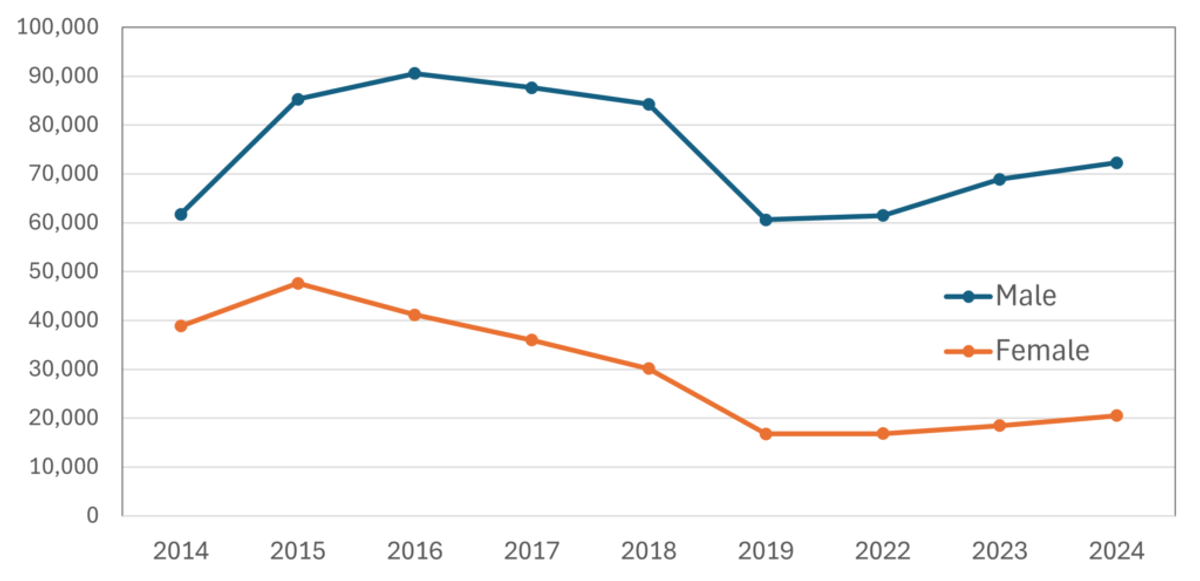

Figure 1 shows the number of students who sat the GCSE Computing (formerly ICT) exam in the last ten years, excluding 2020 and 2021 when public exams didn’t take place. Table 1 then shows the cumulative percentages of students that got a grade 7/A (or 4/C in brackets). Both data are broken down by gender.

Figure 1: Number of GCSE Computing (and ICT till 2018) entries for male and female students in England.

| Gender | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| Male | 22.6% (64.4%) | 20.5% (64.1%) | 19.5% (59.6%) | 19.5% (59.4%) | 20.0% (60.4%) | 20.6% (61.7%) | 32.2% (74.1%) | 22.9% (62.8%) | 26.4% (66.3%) |

| Female | 29.1% (71.9%) | 27.5% (72.3%) | 24.4% (62.7%) | 25.4% (65.6%) | 24.2% (65.0%) | 24.9% (66.2%) | 40.6% (79.4%) | 29.9% (71.5%) | 35.0% (75.6%) |

Table 1: Percentage of students who got grade 7/A (4/C) in GCSE Computing and/or ICT in England from 2014 to 2024. Source: JCQ

The findings are stark. Less than one in four GCSE Computing (ICT) students are female and the gap seems to be widening. Girls constituted only 21% of the 2023 GCSE Computer Science cohort compared to 43% in 2014 GCSE ICT. However, female students have consistently performed better than male ones. This year, there was nearly a 10-percentage-point difference at grade 4+ compared to the 4.5-percentage-point difference in 2019. This contrast in entries and results continues at A Level where less than one in five Computing students were female, but where they also outperformed their male peers.

So, if female students do better, why are they not selecting Computing? Some of the reasons we hear from teachers and students include curriculum changes, career aspirations, learning environments, and inadequate professional development for teachers.

Given the widening gap, many have pointed the finger at the 2014 computing curriculum change. Research shows that roughly three-quarters of girls report not enjoying computing compared with just over half of boys, and fewer girls than boys feel the subject aligns with their career plans.

Interestingly, girls in single-sex schools were over three times more likely than those in mixed schools to take GCSE Computing, suggesting a potential difference in learning environments. It is also worth noting that the proportion of female computing teachers is well below those in other STEM subjects.

So how could we reverse this, and what might the impact be if we did? Let’s crunch some numbers. Say the number of female students rose to match the number of male GCSE Computing students, then over 50,000 more students would be added to the computing education and skills pipeline. On average, about 21% of GCSE computing students go on to study it at A Level. Therefore, this increase could add nearly 11,000 students to those taking the subject in KS5. When you then consider that the number of vacancies in the top occupation most relevant to Digital and Computing stands at 11,297 – 11,000 is a very significant number indeed.

And change is achievable. Other nations have implemented strategies to boost female participation in tech, such as the Singapore Women in Tech initiative, where 41% of the tech workforce is female. Japan, another top STEM innovative leader, has made Informatics I, which includes programming, a required course in public high schools.

In England, increasing female participation in Computing could be done through the ongoing Curriculum and Assessment Review, by broadening the curriculum to make it more appealing to a wider range of students and by reviewing its relative difficulty to other subjects. Girls might find Computing more interesting if aspects of the curriculum included topics like “digital media, project work and presentation work”, as research shows they value “collaboration and teamwork” more highly than their male peers. Ultimately, it will be important to ensure the subject content is relevant to girls as well as boys – not based on preconceptions of what that might mean but based on real life evidence of young people’s attitudes and preferences.

Other ideas include recruiting, training, and supporting teachers through subject specialism training courses like those in maths and physics; fostering inclusive learning environments for all; and breaking down long-held stereotypes about the world of computing education and work. Whichever solution is chosen, the potential prize is clear – propelling the UK to being a tech superpower.