The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there

A levels: Were they harder then or marked more leniently now?

A level results day is all about the future for the young people involved.

But for the older generation it is about the past.

For them, 'exams were much harder in my day’.

The two sides of that coin are firstly, they got worse results than today’s students and secondly, everyone is getting A’s these days.

But how much scrutiny can these arguments stand?

A level: The numbers taking them now distort perceptions

On the first point, Jeremy Clarkson famously – as he has told us every A-level results day since 2014 – left school with A level grades C, U and U.

He says that it was no barrier to getting an expensive car, being on a boat, or doing whatever jet-set activity he is up to this year.

In that very specific and narrow way, he is correct, but as you probably expect it’s much more complicated than that.

One key fact which I don’t see many people talking about is the change in how many people take A levels.

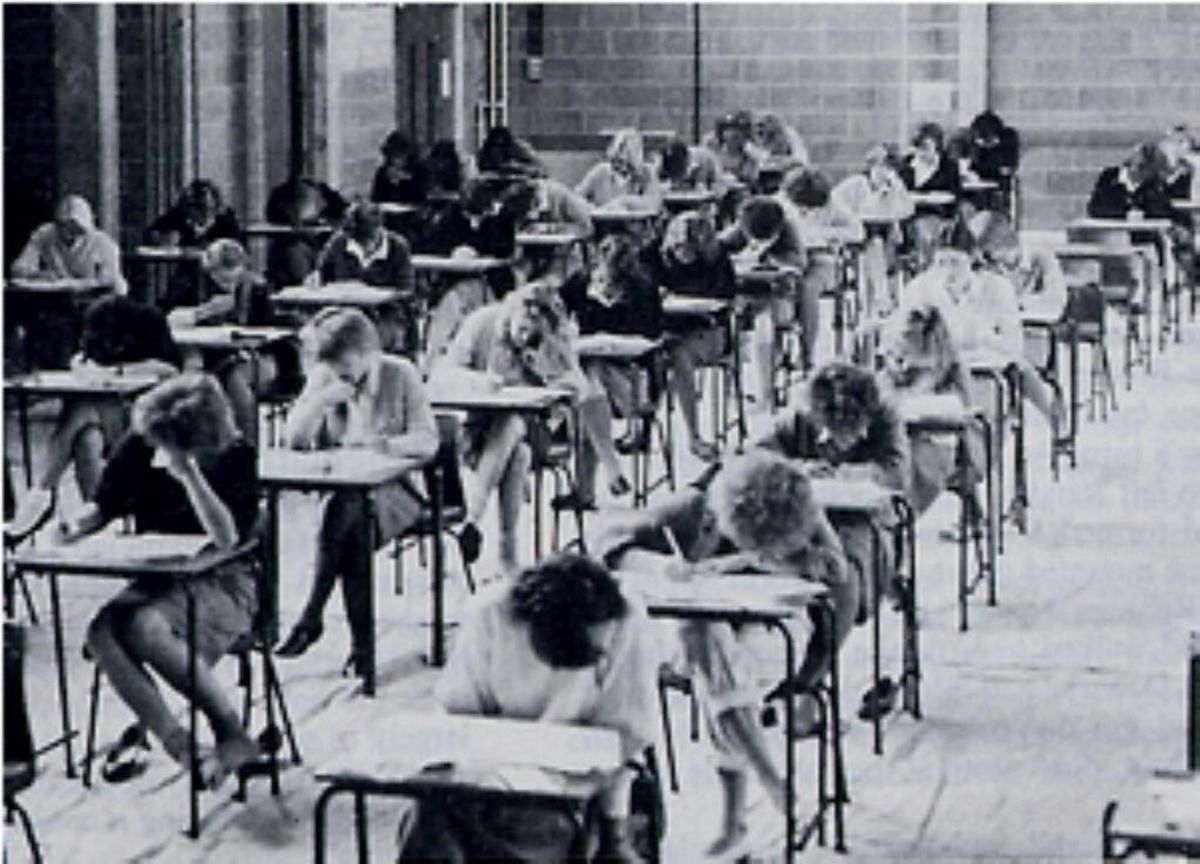

From the 1960s through to the mid-1980s, only around 5-10% of students undertook A level study.

Nowadays it is closer to half.

It means that those who took A levels between 1963 and 1987 and walked away with a C and two U grades, were in the top 10% of most qualified people in the country.

If they were to get similar marks today that would put them closer to the 50th percentile of the highest qualified.

That is the effect of not having the luxury of being part of a small cohort.

So, the meaning of A level results is far different today than it was in the past for the lower achievers.

But what about the second lament? Does ‘everyone get A’s these days’?

Are A levels being marked more leniently now?

To get to the bottom of this, we need to take a little stroll through the history of how grades were awarded.

How do you get an A?

From 1963 until 1987, a grade allocation quota system existed whereby 10% of A level candidates would get an A, 15% a B, 10% a C and so on.

This ensured only a relatively small number would achieve the top grades. It also meant the standard of an A grade may fluctuate each year according to the cohort’s level of attainment.

Nowadays, A level grades are calculated in a different way: neither fully norm-referenced nor fully criterion-referenced.

As I mentioned earlier, A levels used to be for only the highest-achieving 10%, whereas today around 50% of the population sit them.

As Daisy Christodoulou notes, keeping the gradeset at the same standard after such an expansion in numbers would mean a large chunk of students failing the exam.

Is it harder to get top A levels today?

This year, around one in 11 (8.9%) of entries received an A*.

Doing some quick maths, 8.9% of 50% works out at less than 4.5% of the overall population getting highest grades, compared to 1% back in the day.

On the surface this may look like a big change, but we need to consider that in previous generations, some students who didn't do A-levels would have been perfectly capable of succeeding on the course and getting high marks.

Applying the old framework of the top 10% get the highest mark would mean that closer to 5% of 18-year-olds would get an A*, which is not too far off the 4.5% figure of today.

So, it simply is not the case that “everyone gets As” these days.

What is under-examined is the sheer demographic change.

More people are achieving top grade A levels than in the past, because more people are sitting them, but the proportions of top grades are comparable.

So, it seems that A level standards haven’t changed that much, after all.

What has changed is the sheer size of the cohort sitting them. A levels have changed what they do and who they are for.

Perhaps some commentators would do well to brush up on their percentages.

One final point, well done to everyone on their results whether they got a Clarksonesque CUU or A*A*A* - neither of which I achieved.

Read more on this subject:

Grade Boundaries: Getting back to normal after the pandemic

Could comparative judgement replace traditional exam marking

Making the grades: Turning an exam into a qualification

Read more by this author:

Text anxiety does not predict exam performance

Social isolation linked to reduced academic success

Music and attainment: What do we know