Reading age tests - blunt or sharp?

Photo by Markus Spiske/Unsplash

You probably think you’re pretty literate, don’t you?

You’re on a specialist research website, taking in the latest thinking from the education world, so you must be able to read to a high level, surely?

But, chances are if you took the standard reading test today you’d be assessed as having the same reading age as an average GCSE student.

Surprised? Think the test must be flawed? You might just be right.

What is the role of reading age tests today

Reading ages - a handy tool or blunt instrument?

Consider this. A newly-arrived Year 5 teacher is in the school library with his class. He barely knows the pupils so pulls out a handover sheet matching each child to a reading age.

One by one each is sent to look at books bearing the appropriate coloured sticker. Most read at the level of an average nine-year-old, a handful are higher and a similar number lower.

What does that reading age actually mean?

Is a reading age only words or does it go deeper?

Well, by Year 5, a youngster usually has an everyday vocabulary of about 5,000 primary everyday words they use most frequently, and a secondary set of 10,000, which are less commonly used but still understood.

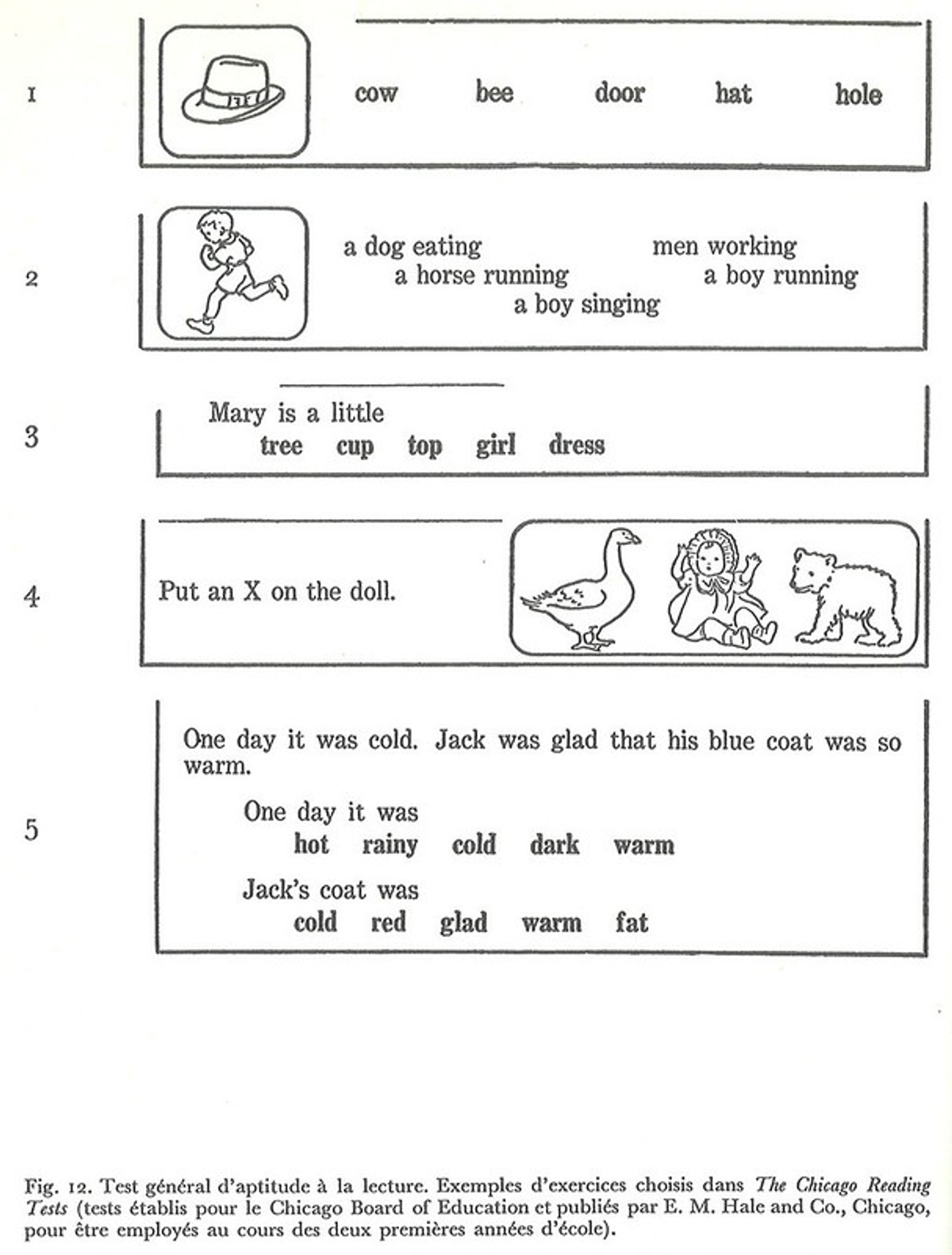

Finding the reading age, in its simplest form, involves asking an age group to read a list of words ranging in difficulty from, say, ‘hat’ to ‘doubt’, to get an average score.

Chicago Reading Test - Flickr

But the problem with using reading ages is primarily that they don’t paint the whole picture of a child’s literacy.

Do you have the reading age of a nine-year-old?

The Department for Education’s list of expectations of children at KS2 is too complex for simple reading ages to be a meaningful measure.

Pupils between nine and ten should, among other things, be:

- showing comprehension of words in context

- inferring characters’ feelings and thoughts with evidence

- distinguishing between facts and opinion

- reading and discussing fiction, poetry, plays, non-fiction

- recommending books with reasoning

It’s demanding stuff. The Sun newspaper has a reading age of nine. The Guardian’s is 14. Even the official Gov.uk website advises authors to write for a nine-year-old reading age.

Reading Age: A stigma or a useful signpost?

Years later, at KS4, a 16-year-old is assumed to have all those KS2 skills and be a fluent reader, who may need to look up the odd word.

Here lies the starkest example of the measure’s limitations – this is the age at which the measurement halts.

So even the most literate adults are only ‘reading like a 16-year-old’.

Critics say it’s simplistic, stigmatises the learner and affects their teaching. Supporters say it is a well-understood guide to a student’s learning.

It is clear they don’t give a sophisticated analysis of literacy, articulacy or comprehension which may be unhelpful when the government is trying hard to raise adult literacy in the UK.

On-screen adaptive assessments - measure and teaching aid?

This is where the growing number of on-screen adaptive assessments could step in.

On screen adaptive assessments are increasingly used in schools

Photo by Annie Spratt/Unsplash

Some use multiple-choice questions to assess vocabulary and comprehension using a range of texts from single sentences to short passages.

Others measure phonic ability using audio questions to identify word structures.

On-screen adaptive assessments can also test phonic ability

Photo by Ben Mullins/Unsplash

Grammatical and inference skills, and the handling of abstract language, are also tested.

Because the on-screen tests are adaptive, question difficulty changes according to the student’s previous answers to ensure they are not too easy or hard. This means finely scaled scores can be calculated.

These can then be used to track progress against expectations and teaching plans.

While they are less stigmatising, they are also arguably more opaque.

Telling someone that they, or their child, reads at ‘238’ needs far more explanation than saying they have a reading age of nine.

Old and new can work together

So maybe there is still a role for reading ages – used alongside other on-screen adaptive assessments, they could be useful.

They are a good rule of thumb, easy to understand but not an accurate measure of a person’s reading skill.

The direction of travel is all important

Photo by Moodycamera/Flickr

Like a landmark on the skyline, reading ages can help with gauging position and guiding general direction.

It’s when you’re close to the destination that you pull out the map to get the fine detail.

Read more on this subject:

Assessing Oracy: Is comparative judgement the answer?

Progress 8: Schools' flexible friend?

Digital Exams: A chance to make assessment more accessible for all