Estonian pupils study using some of the most up to date educational tools in the world

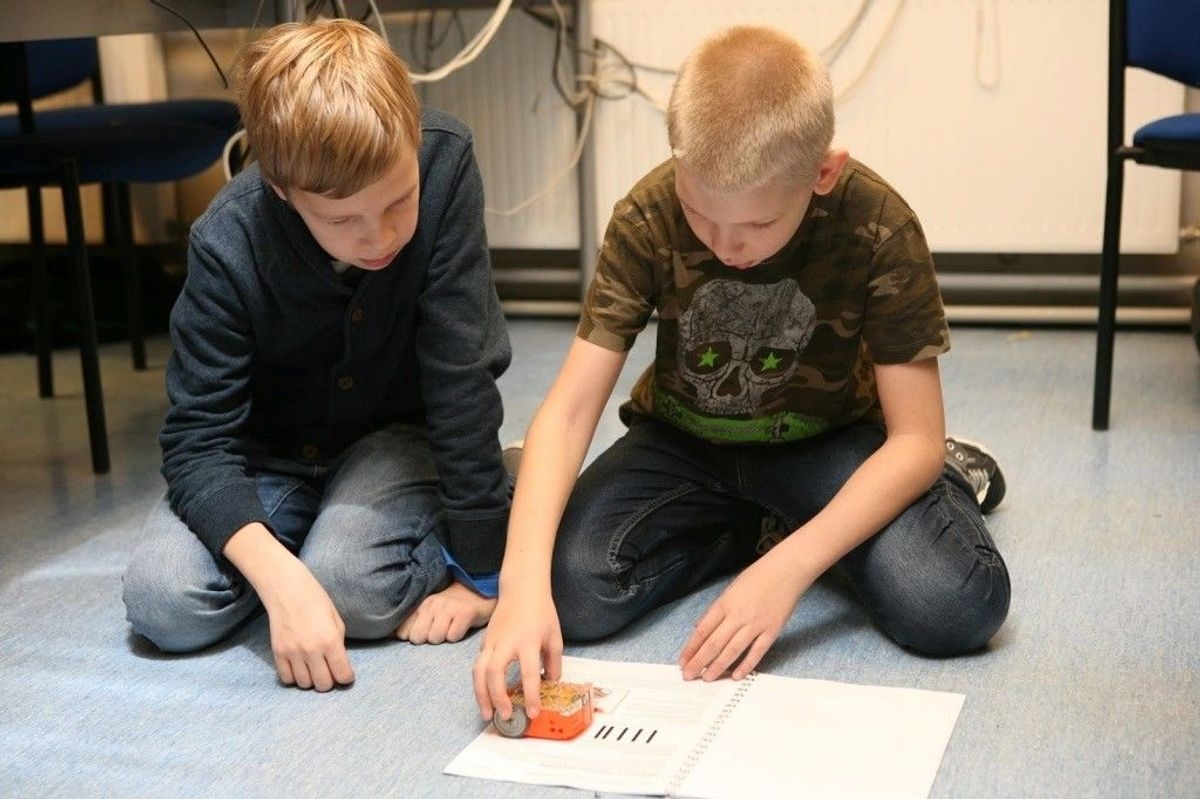

In one classroom, robotics lessons are delivered to seven-year-olds. Next door pupils wear virtual reality headsets to enliven a geography class.

And down the corridor in the staffroom a teacher and parent meet online for a weekly catch-up session to analyse their child’s performance data.

You may think that this is an academy for the ‘gifted and talented’ but it’s not. This is a standard Estonian public school.

Estonia's Tiger Leap into the digital world and educational success

Since 1996, when former President, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, and Education Minister, Jaak Aaviskoo, unveiled Tiger Leap – an ambitious plan to modernise Estonian society – the country has focused on moving its schools away from traditional learning tools such as paper textbooks and whiteboards towards computerisation, the internet and digital tools.

Tiger Leap deliberately drew on the country’s well of expertise built up before the fall of the Berlin Wall, when it was a hub of Soviet computer manufacturing.

By 1998, 97% of schools were connected to the world wide web and most had swapped their outdated Juku computers for IBM models. Two years later, every school was connected to the internet.

Digital versions of all educational material – textbooks, workbooks and other learning tools - had been created by 2015.

As a sign of how digitally literate Estonian society is, nearly every direct public service in Estonia – such as voting and paying taxes – is available online and 93% of the population access them using secure eID cards or mobile phones.

Estonian digital classrooms

Today, all pupils can work on iPads or classroom computers using dedicated software, apps and digital hardware, including virtual reality headsets.

Every public school uses a comprehensive ‘Learning Management System’ such as eKool or Stuudium.

Advocates say these bespoke edtech tools – created by the Estonian private sector in collaboration with schools – together with intense professional development of teachers and educational technologists, are the cornerstone of the country’s educational success.

They allow educators, pupils and their families to study, communicate and organise efficiently.

Estonia's schoolchildren have their head in the cloud

Students have ‘e-schoolbags’ where all their learning materials are stored in the cloud. Hard copies are available for those who want them.

They submit assignments online and store their portfolios there too.

Because all work is done and marked online, extensive progress data can be collected and analysed showing exactly how an individual is performing.

Estonian children studying robotics and informatics in class

Data driven teaching and interventions

School staff do the data entry which is then open to scrutiny by teachers, parents and children.

Among the information available are lesson topics and homework, individual grades, timetables, attendance records and school news.

The statistics lead to swift, fine-tuned feedback and interventions where necessary.

Formative assessment is used to mark academic progress on a regular basis. Students are assessed every three years against set criteria in which even their attitudes, behaviours and values are considered.

The feedback from these assessments creates the base of an individualised future learning programme.

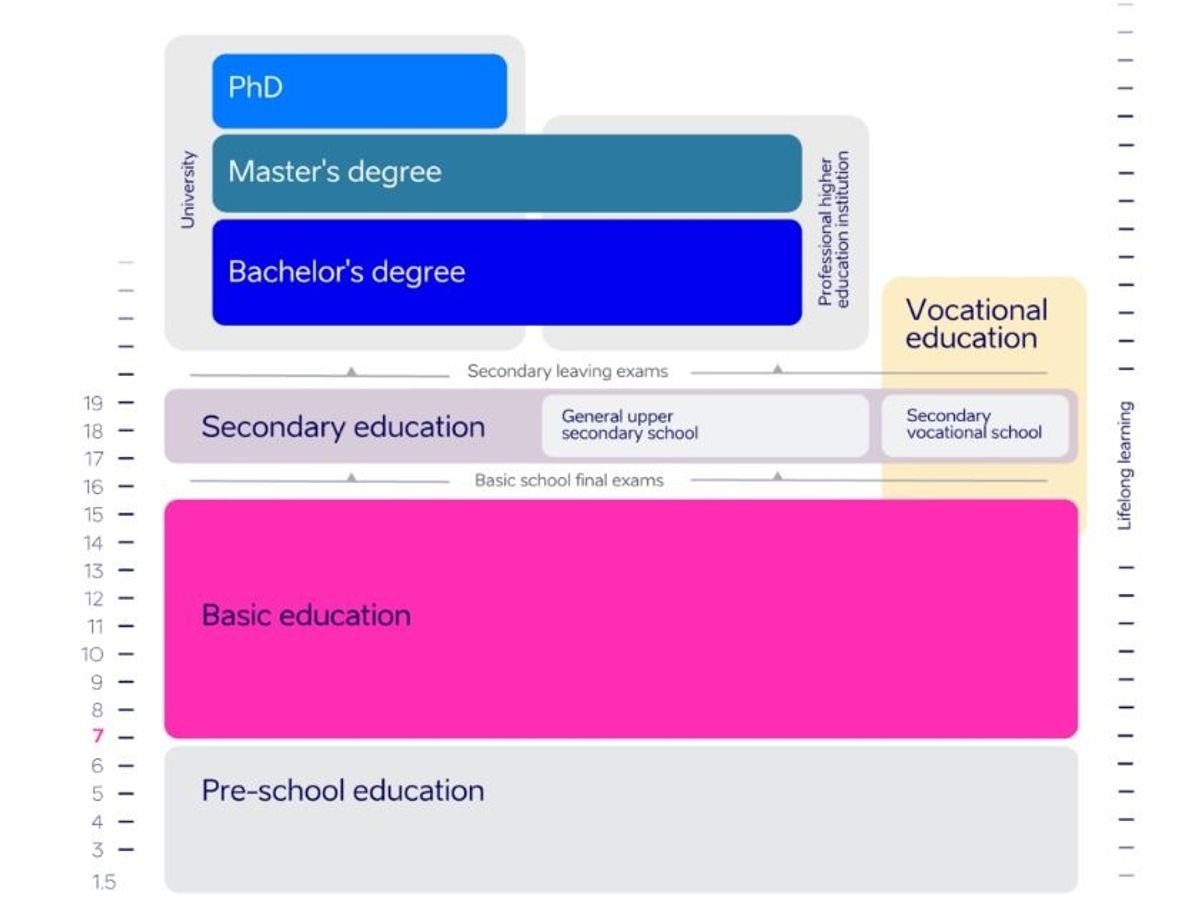

Estonian examination system

The first national exam students sit come when they are 17 at the end of their Basic schooling. They sit three internally marked papers – Estonian, maths, and a third chosen by the student.

All three have to be passed and a creative project completed before they can enter Secondary education.

Those opting for academic Secondary education take four exams at 19 - Estonian, maths, another language and a General Secondary School Exam.

They also complete a research paper or practical work carried out over the three years.

Graduating allows them to move into Higher Education.

Those on vocational courses take part in work placements of up to 50% of learning hours and then sit professional qualifications.

How are Estonian schools and teachers assessed?

External inspections used during the Soviet era were replaced with self-evaluation by principals.

These cover perceived weaknesses and used to devise a School Development Plan along with input from teachers and students.

Teacher assessments are also carried out by principals.

Teachers have a 35 hour statutory working week and at Secondary level 63% of teachers’ working time is formally dedicated to non-teaching activities.

Holding Estonian education system to account

On the surface allowing schools to mark their own students’ exams, carry out internal assessments and teacher evaluations may appear to lack transparency.

But, as with almost everything in Estonia, all the data can be revealed at the click of a mouse on an open access database.

The academic performance and characteristics of each school are constantly evaluated and the results are fully public.

This helps the best performing schools attract more pupils and in turn more funding.

A programme of school closures to account for falling student numbers means that the worst performers are shut down.

Estonia's education success: The takeaway

Estonia’s success appears to be based on the digital education revolution which started from a strong base.

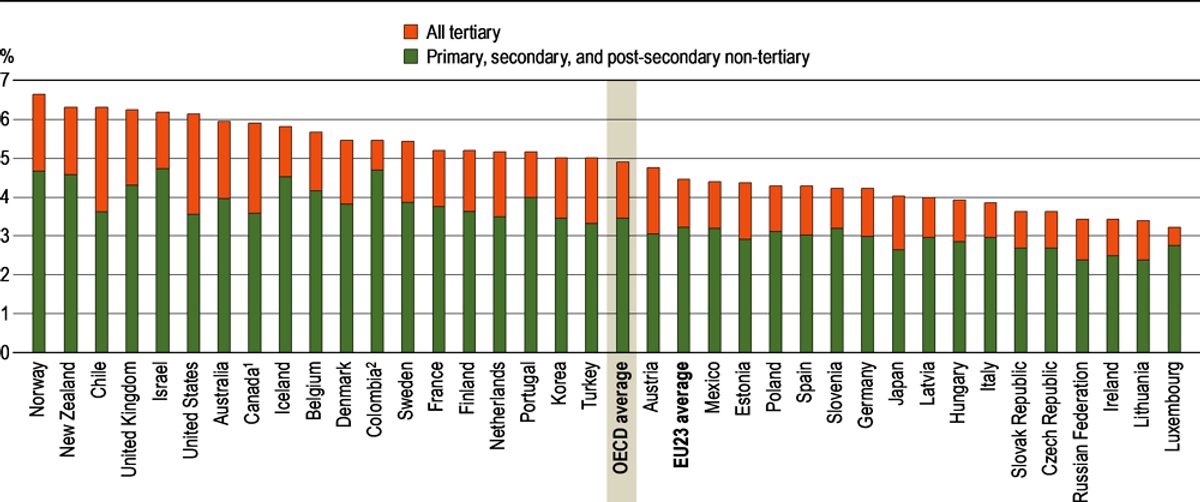

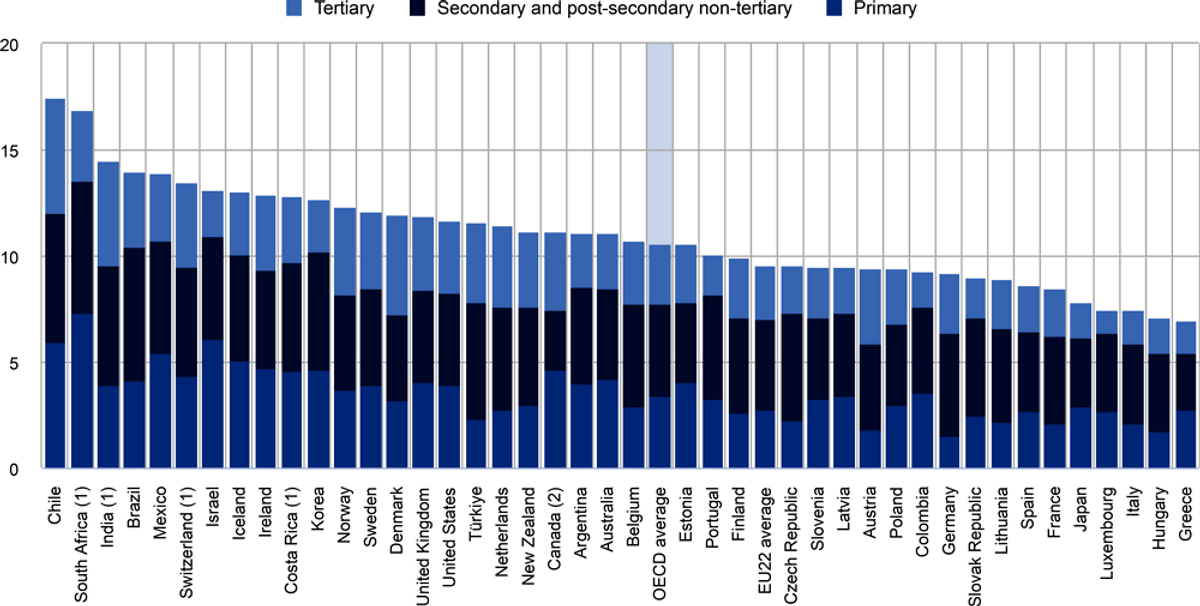

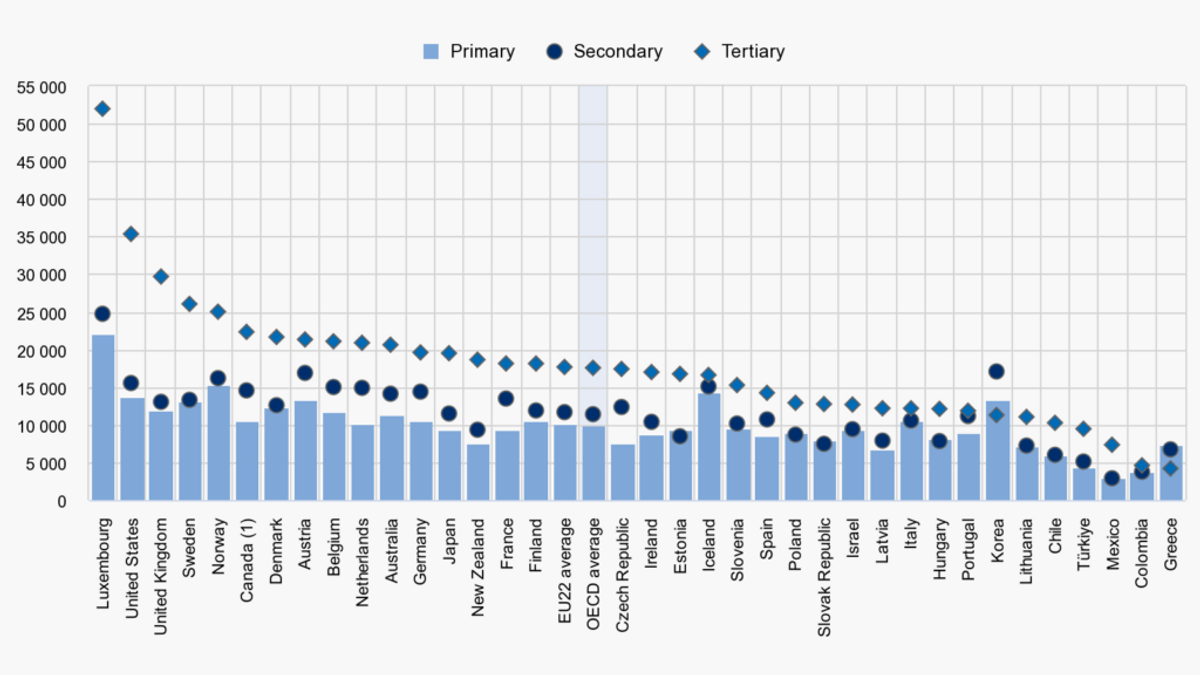

But it has to be said that money does not seem to have been a deciding factor.

There is much that educationalists and policymakers can learn from studying what the former Soviet state has achieved and the way it has done that.

Read more about this subject:

Simulation Assessment: A future tool for today? | AQi powered by AQA

Can digital technology transform assessment practices? | AQi powered by AQA

Who is responsible for Digital Literacy? | AQi powered by AQA

Read more on foreign perspectives:

Finland: Going against the global trend | AQi powered by AQA

Digitising a country’s examinations | AQi powered by AQA

Singapore: probably the best organised education system in the world | AQi powered by AQA