Carrying out science practicals benefits teachers as well as students

The value of classroom practicals

I fell in love with chemistry in my A-level studies at Carmel College in St Helens.

An incredibly passionate, slightly eccentric, red-haired teacher called Cheryl inspired me with her wild enthusiasm for practical science.

I have fond memories of the friendly competitions getting out our conical flasks and pipettes and trying to match Cheryl's accuracy titrating solutions to find the concentration.

How science practicals worked in lockdown

Fast forward 10 years, I was teaching those same practicals, but this time during an unprecedented situation – lockdown.

It was challenging due to the lack of experiments. I did on-camera demonstrations to try to enthuse my students, but science is all about hands-on exploration.

Part of scientific investigation for students is to solve problems as they arise. Experimental failure teaches them about the scientific process, which develops resilience and fosters innovation.

While it was amazing how teachers stepped up to the challenge and learned to use new digital tools and teaching platforms, in science, nothing can replace experiential learning.

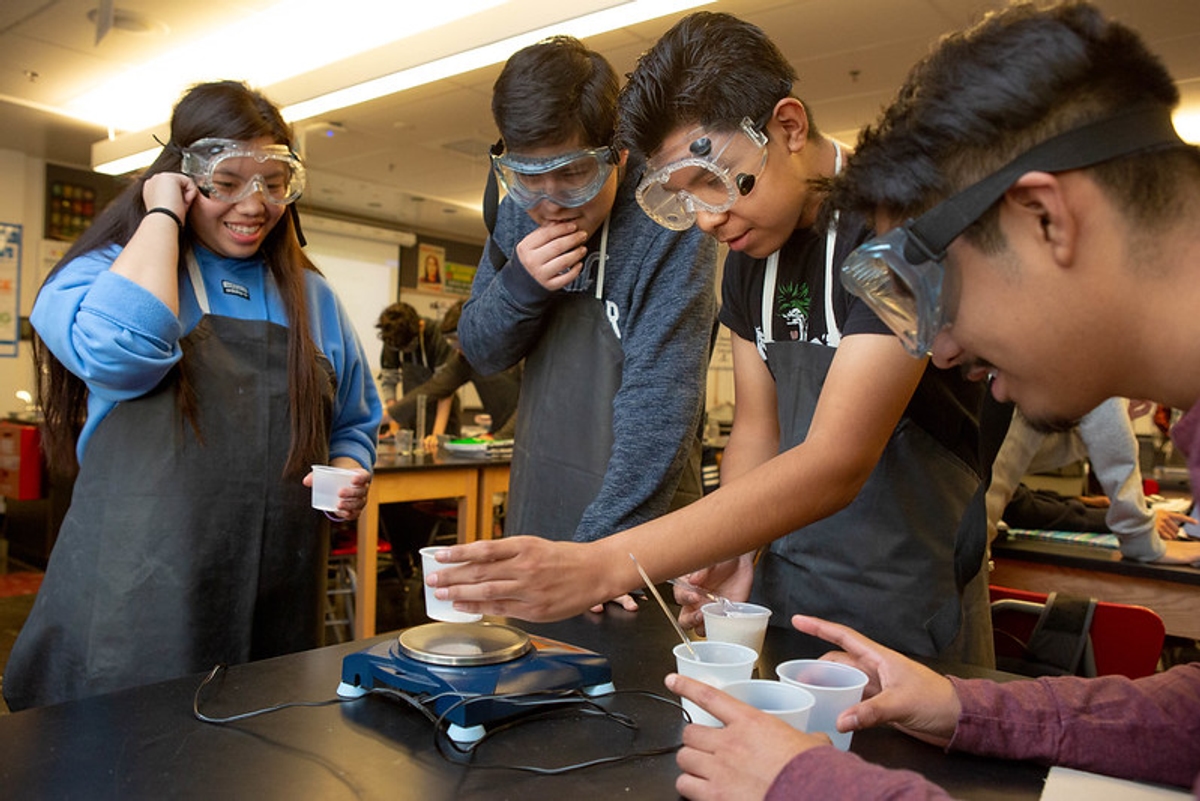

Hands on experimentation teaches students more than just how chemicals react together

Photo by Allison Shelley for EDUimages

It is clear that a lack of practicals impacted learners’ development.

Evidence from an AQA research project with the University of Durham revealed that A-level students felt their soft skills, such as referencing and researching, had developed through lockdown.

However, they said their ‘hands-on’ manipulative skills were under-developed. Videos or online simulations were simply unable to bridge the gap.

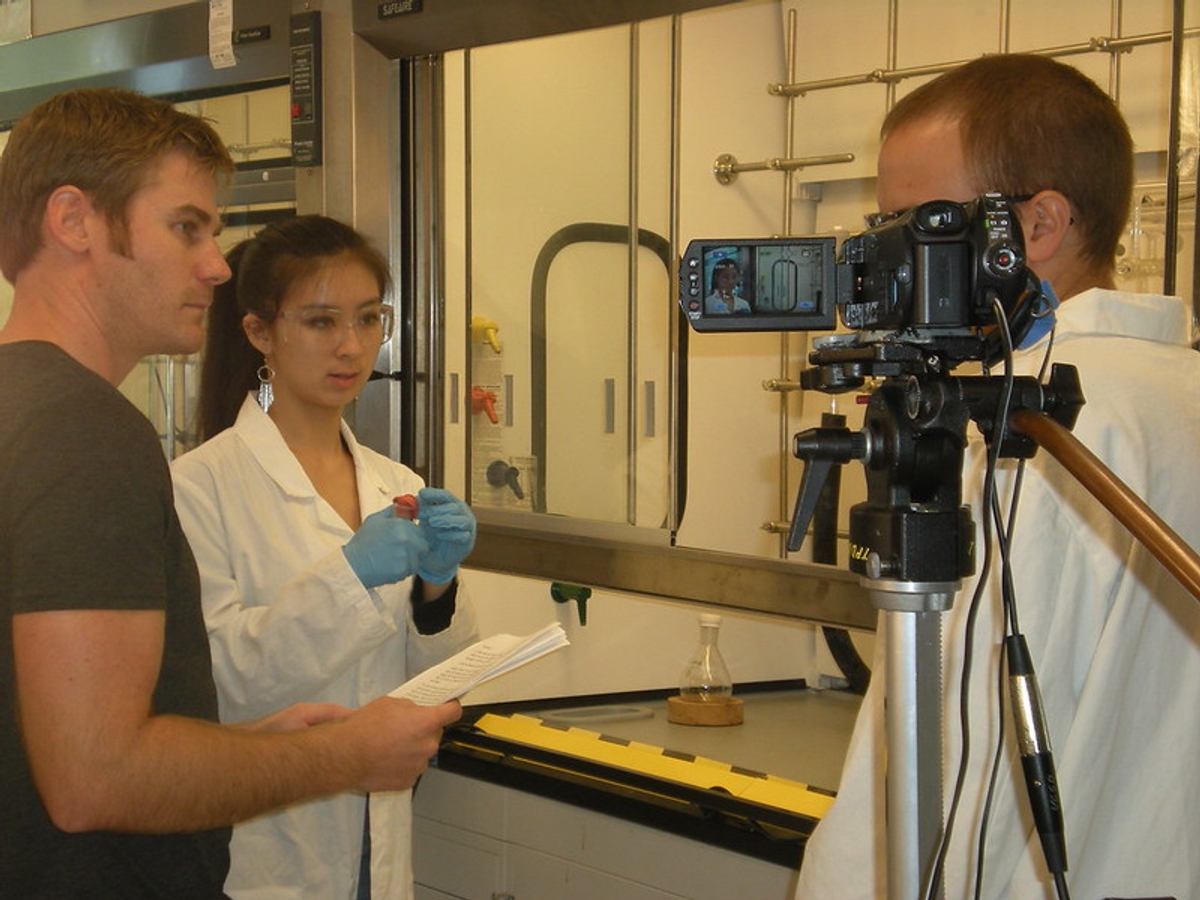

Videoed practicals served a purpose but cannot replace the real life experience

Photo: Alex Hansen/Flickr

The reliance on simulations and online demonstrations...should not become a permanent feature of science teaching.

Losing hands-on practicals is not just an issue for students

What is less well known is the impact of lockdown on teachers' development.

A Royal Society of Chemistry study released this year found that, as a result of the pandemic, 55% of trainee teachers and 46% of first year teachers felt completely or quite unprepared to teach practicals.

Some 82% and 67% respectively wanted additional training on teaching practical science.

Not surprisingly, trainees who moved on to be Early Career Teachers (ECT) without having led practicals have felt far less confident delivering, or overseeing, classroom experiments.

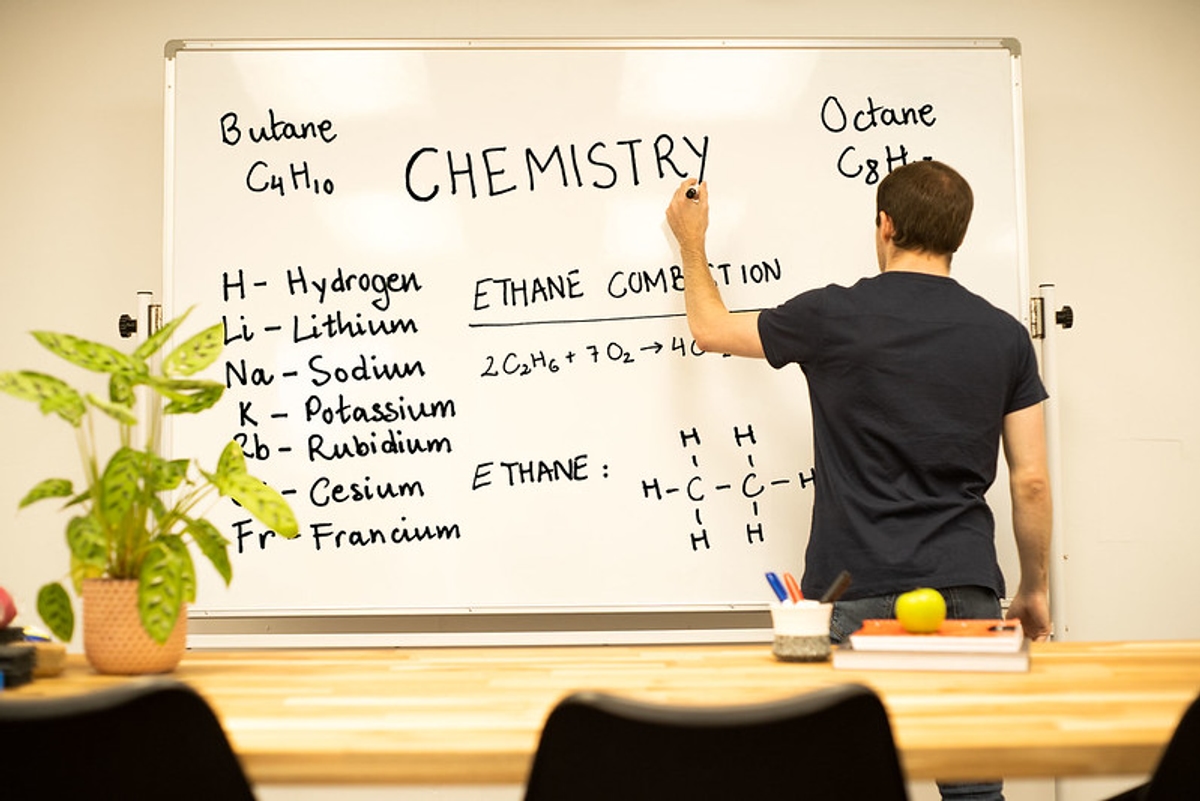

The use of science videos and simulations rocketed during lockdown

Photo: Preply.com

In fact, training providers found some ECT actually feared holding practicals, due to limited experience and lack of in-lab training.

The reliance on simulations and online demonstrations at the expense of in-person classroom practicals should not become a permanent feature of science teaching.

The value of delivering hands-on practicals for teacher development

Throughout my career I have mentored many trainee teachers. More recently I trained as an instructional coach with the Ambition Institute for its ECT pilot programme in 2019.

I saw first-hand how evidence-based professional development had a positive impact by modelling bite-sized content in deliberate practice, allowing ECTs to rehearse in front of mentors and improve through feedback.

Last year, for my MSc research on team development in education, I spoke to the same programme’s participants about their experience since Covid-19.

What do the teachers want?

All the science teachers I surveyed said they would value coaching sessions on delivering practicals with experienced staff, particularly teaching outside of their specialism.

This is why as part of the Big Experiment Week, we have science teacher, Katy Webb, providing video masterclasses for teachers linking practicals directly to the AQA specifications.

Masterclasses for professional growth

My experience leads me to believe this approach could effectively be incorporated into schools' science Continuing Professional Development (CPD).

It could bridge gaps for teachers trained during the pandemic and act as a refresher for those who need it.

If education leaders ensure their institutions’ cultures encourage teachers' confidence in sharing their weaknesses, they will seek opportunities to address them.

Fostering a growth-mindset among staff, giving them access to high-quality CPD, and time to develop their self-efficacy in delivering practical science will improve teacher retention.

Exciting practicals were partly what led me to a career in science.

Keeping them intact is imperative for the good of students, teachers and the long-term health of science education.