The quiet revolution within one of the world's leading education system continues with a new agenda for rapid change

Major political speeches in Singapore are a different beast from those in the UK.

Forget hyperbole, emotive ideology, and repackaged spending announcements to create a punchy next-day headline.

Instead, listen carefully to measured words and a McKinsey-like vision for the long-term.

Singapore's education minister Chan Chun Sing revealed his reforming vision at the Institute of Policy Studies Singapore Perspectives 2023 conference

Photograph courtesy of IPS/Jacky Ho

Chan Chun Sing, Singapore’s Minister of Education made such a speech at the beginning of this year to Singapore’s leading think-tank during a conference focused on the future of work.

“Education is a long-term endeavour” he stated early, emphasising evolutionary continuity, about which AQi has already written.

But this was a quietly radical speech explaining that Singapore’s education system must change ever more quickly away from its legacy of structured, traditional rote learning.

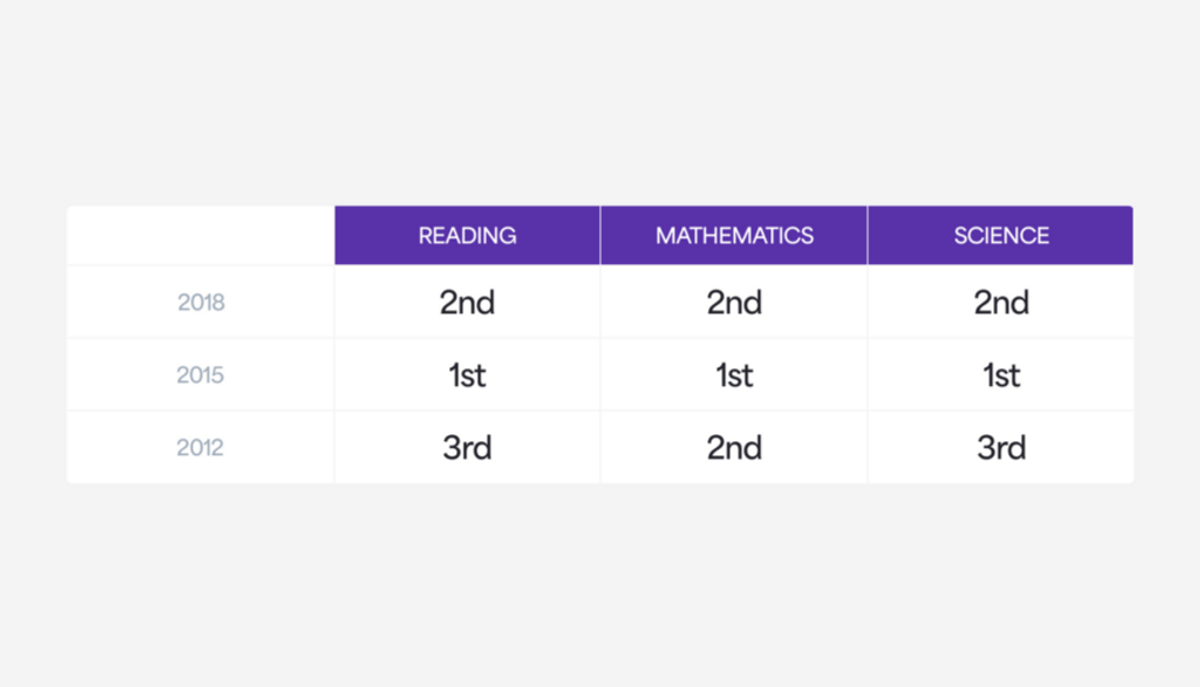

It was a calm, careful kick to the system that has delivered some of the best PISA scores for a generation.

Singapore has an admirable consistency in the OECD's education PISA rankings

“The urgency for our education system to evolve at speed is clear,” he stated.

Singapore’s strategists have decided that to achieve continued national success, the speed of change in educational attitudes, priorities and approaches must increase dramatically.

This is revolution by stealth as Singapore seeks to hold onto the rigour and commitment of its traditional educational structures but let loose a wide range of new attitudes and behaviours.

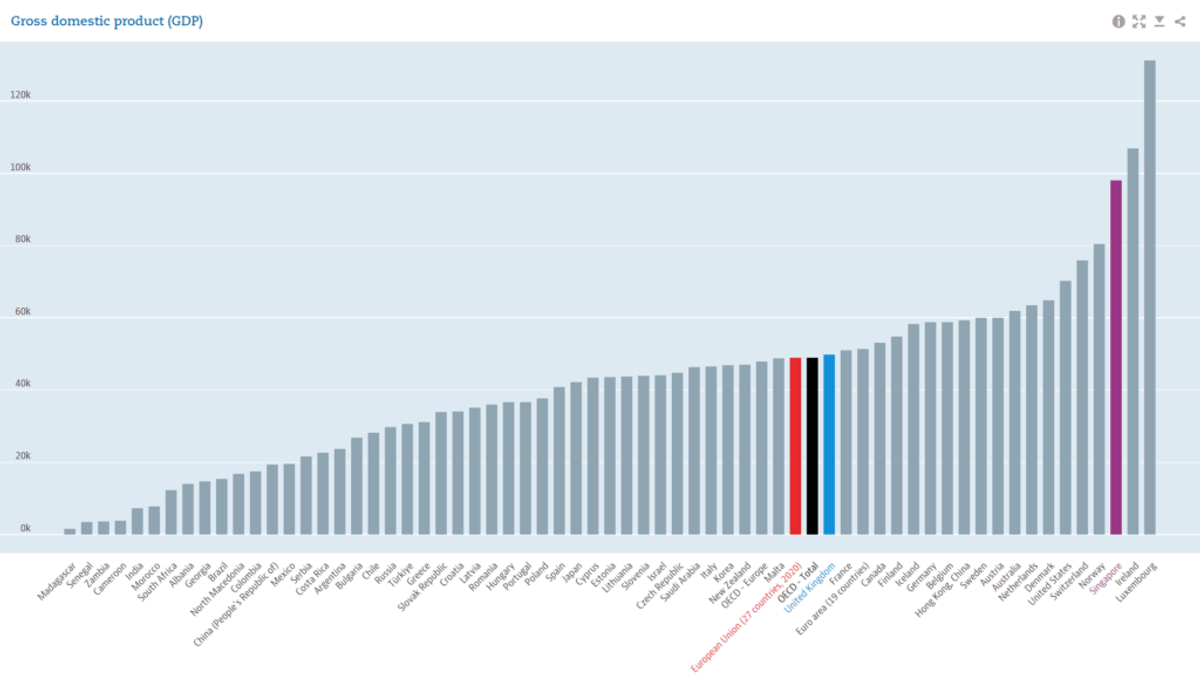

Education has been at the heart of Singapore’s development since its independence in 1965.

Then, Singapore was a poor country with very low rates of basic literacy. Since however, through a carefully evolved national strategy it has achieved remarkable economic success with GDP per head now more than twice that of the UK, according to the OECD.

So when the Minister of Education says that it is time for such significant educational change - and is willing to take significant risk to achieve it - it is worth taking notes.

Why the urgency Minister Chan?

Chan Chun Sing paints a picture of “a more connected, yet fragmented world.” It is a worrying, unpredictable place. Such concerns can increasingly be found in landmark political speeches across the globe.

Minister Chan's words should make educationalists across the globe sit up and listen

Photograph courtesy of IPS/Jacky Ho

More interestingly the Minister picks out challenges that he feels the education system must try to address:

- Citizens will not prosper, without strong digital skills. Educational and social structures must build these skills for all.

- Knowledge is important but it is a commodity. Anybody will be able to access and use it. Without education also building curiosity, creativity and collaborative skills, society will not prosper.

- Greater inequality mixed with a global web of uncertain digital narratives will create greater tensions within and fragmentation of society. New generations must have the skills to “understand the world as it is” and not simply adopt the narratives of others.

- Greater human competition with the “shelf lives” of jobs and skills reduced to years rather than decades. The ability to innovate personally and acquire new skills will be essential.

- Singaporean society must be more open to outsiders and to their cultures and attitudes, which will be key to the country’s future success. Singaporeans must not “turn insular, nativist and retreat into our own echo-chambers.”

What will change Minister?

Singapore’s education system has been gently reforming for over a decade but in this speech Chan Chun Sing put the whole system on alert that change will now be deeper and faster, challenging more fundamentally long-held educational priorities.

Curiosity and Critical Thinking

The teaching emphasis will move further, faster towards analysis and critical thinking. Curiosity, creativity and co-operation were the words repeated in the Minister’s speech.

By contrast, there was the simple blunt recognition that “knowledge is increasingly commoditised.”

This is a man with a first in economics from Cambridge and an MBA from MIT.

Commoditised products are, as we know, low value. When your product is being commoditised, it is time to move on to other higher-value areas.

The value, he believes, is in new areas that are harder to teach so although “we cannot teach curiosity or creativity, we must not diminish them through rote learning,” he continues.

The Singaporean educational tide has been moving slowly in this direction for a decade; now he seeks a sea change.

Grades could become less important than creativity and team-work to secure a university spot raising the social importance of these attributes

Photograph of Singapore University of Technology and Design courtesy of Scott Chu/Flickr

Levelling up

Concern about the risks of growing divisions within Singaporean society run through the speech.

The Singaporean government has always intervened to address divisions in society created by disparities in wealth and differences in ethnicity.

The race riots around independence left deep scars. Social intervention is a central pillar of government policy.

Lee Kuan Yew, the former prime minister who spent 31 years in office overseeing the growth of Singapore, campaigned for the Labour Party while a student in post-war Britain. Its public housing (80% of Singaporeans live in state-built housing) and public health programmes are among the best in the world. Attlee, Morrison and Bevan would be at home with many of the values in Singapore’s government.

Now Singapore will invest more money and resources into the early educational years, focused on less privileged families.

It will coordinate social and educational support, piloting new approaches – the test and learn approach that has similarly defined previous initiatives.

The objective is a simple one: to level up the educational achievement levels of less privileged children to give them greater opportunity in the long-term. The less privileged must benefit from the success of the ‘Singapore Story’.

Since Chan Chun Sing grew up in a single parent household and his mother was a machine operator, the commitment carries the credibility of personal experience.

Upskilling Teachers

Singapore has always focused on the quality of the teaching cadre as a central strategy.

This is an enduring theme since the earliest days when there simply weren’t enough qualified teachers to support universal education in the first decade of independence.

The Minister looks to teachers to explore and develop new pedagogies that will achieve the new objectives he is sketching out.

He wants teachers to be exposed to the changing world of work and to be trained to bring new, up-to-date perspectives into the classroom.

Singaporean Teachers will have to undergo their own reforms to fit in with Minister Chan's vision

Photograph courtesy of Education International

They do not have precise answers yet buy will find ways to develop teachers with wider experiences and skills to bring new approaches and learning structures into the classroom to encourage curiosity, critical thinking and relevance in an inter-connected world.

Broader Entrance Criteria

Access to higher education in Singapore, be it university or polytechnic, has always depended on your grades. Other aspects of applications have been hurdles to cross, little more.

Wider assessment of aptitude, commitment and potential will become more important as the Minister uses this lever to achieve a wider change in educational thinking “away from the incessant desire to compare and benchmark both students and institutions.”

If grades are less important – and, say, demonstrating creativity, entrepreneurship and team-work are more important - in securing that top university place, these atributes and skills will become more important throughout Singaporean society.

The Minister is using another lever of state to try to change educational priorities across a nation and grow the attitudes and skills that don’t necessarily come out in test scores.

Mass Customisation

This concept is less developed. It is one that the Singapore system will weave its way towards through experimentation.

The objective is simply to develop increasingly student-tailored curricula that reflect different abilities and learning styles.

Two approaches are currently at the heart of this idea.

Teamwork is likely to be a key skill for the future of Singapore's education system

Photograph courtesy of Dinesh Parate/Flickr

The first is simply extending increasingly tiered academic streaming across more subjects so that students can study at the level that is most appropriate.

The second is no more than a sketch of a technology-driven future where adaptive learning, powered by artificial intelligence, has a major role to play.

It is just a sketch but lays out the challenge for personalised educational development in a world where AI such as ChatGPT will become ever better at answering your individual question.

There is far more in Chan Chun Sing’s speech, which also includes ideas on lifelong learning, students building international friendships, involving parents and community, integrating education and industry more closely and how teacher training and support will evolve.

If you remember just a couple of things from this article, let it be that Singapore’s policy makers have decided that though they have developed one of the world’s leading education systems, they must now turn harder and faster than ever before to maintain the system’s relevance in a newly challenging era.

Chan Chun Sing has thought about it for 18 months and decided the extent of the challenges he foresees justify the risks of change being taken.

To read Minister Chan's full speech click here.

Read more on Singapore

- Singapore: where is the poster child of global education heading now? | AQi powered by AQA

- Singapore: probably the best organised education system in the world | AQi powered by AQA

Read more by Tim Ewington

On-screen exams: what school leaders, teachers and students think (aqa.org.uk)