Assessment

Computer science and on-screen assessment: Lessons for policymakers

Evaluating the barriers and benefits to on-screen assessment among AQA A-level Computer Science teachers.

Executive Summary

There is growing interest among policymakers and teachers in the potential for more exams to be taken on-screen in future given potential benefits for students, the fairness of assessments and the resilience of the exam system.

Despite a small number of existing GCSEs and A-levels in England already using on-screen technologies, there is a shortage of evidence on the pros and cons of on-screen assessment (OSA) that is relevant or specific to high-stakes exams in England.

This briefing summarises a survey of A-level Computer Science teachers, who have experience of their students' sitting, and centres delivering, OSAs. Their views and insights are highly valuable for policymakers exploring the potential for greater use of OSA in the English exam system.

The survey explored their views on a range of issues including:

- infrastructure and devices

- hacking and malpractice

- teaching a qualification with OSA

- the potential for OSA in other subjects.

Key findings include:

- most respondents reported that staff training, and ensuring adequate, working equipment had not been an obstacle in delivering OSA of A-level Computer Science

- over two-thirds said that delivering OSA of A-level Computer Science has not been difficult or challenging

- survey respondents were confident in the feasibility of introducing OSA for smaller, optional GCSEs (86%); less so for larger or compulsory subjects

- two thirds of those surveyed agreed that OSA of other A-levels should be feasible for centres to deliver.

1. Introduction

GCSEs, AS and A-level exams in England are mostly taken using pen-and-paper. However, there is growing interest among policymakers and teachers in the potential for more exams to be taken on-screen.

For example, in a speech on March 23, 2022, the Education Secretary noted:

It's possible that more digital assessment could bring significant benefits to students, teachers and schools and I want to start carefully considering the potential opportunities in this area.[1]

For policymakers, there are complex issues to consider any significant increase in the use of OSAs for GCSEs, AS and A-levels. Consideration of such issues is made more difficult by the shortage of evidence that is relevant or specific to high-stake exams in England.

This gap in evidence is surprising given a small number of GCSE and A-level components are already assessed on-screen. One of these qualifications is AQA’s A-level in Computer Science.

Teachers of A-level Computer Science, who have experience of their students sitting OSAs therefore have views and insights that are highly valuable for policymakers exploring the potential for greater use of OSA in the English exam system.

To support policymakers considering the future of OSA and the exam system in England, this briefing sets out the result of a survey undertaken by AQi of teachers who have taught AQA A-level Computer Science. The survey explored their views on a range of issues including:

- infrastructure and devices

- hacking and malpractice

- teaching a qualification with OSA

- the potential for OSA in other subjects.

1.2. AQA A-Level Computer Science

AQA’s A-level in Computer Science comprises an OSA, a traditional pen and paper examination and a non-exam assessment (NEA) in the form of a computing practical project (i.e. summative ‘coursework’).

For the OSA component, centres download a Skeleton Program and Preliminary Material describing the program's operation at the start of the academic year. The Skeleton program is available in five different programming languages and students experiment with the materials ahead of the examination.

On the day of the exam, candidates log into their centre's network using a special exam login (set by the centre) to which they have had no prior access. They then run their chosen integrated development environment (IDE) for the selected language.

Students are then set a series of questions or tasks, provided on a standard assessment paper. Some question may be theory related and answers are simply typed into the Electronic Answer Document (EAD); a Word document formatted to receive the candidate's responses. Other questions require modification of the Skeleton Program which entails students evidencing their work through screenshots and demonstrating that these changes work, and the changes themselves, which are usually copied from the development environment and pasted into the EAD.

The EAD is then printed, checked by the students and collected by the exam officer who returns the printouts- like any other paper-based assessment- to the exam board.

1.3. Survey methods

All teachers of AQA A-level Computer Science were invited to participate in the survey, excluding any who had chosen to opt out of further communication.

The survey was designed to solely capture the views of teachers who had direct experience of having taught a computer science specification with an on-screen examination.

In total, 104 teachers completed the survey. Very few questions were compulsory out of understanding for how time-pressed most classroom teachers are, so completion rates for individual questions are varied. As a result, the findings are presented as percentages throughout. Participants were asked a mixture of closed, open and attitudinal questions.

The sample of respondents was mixed. Most respondents were departmental heads (69%), followed by teachers (26%) and senior leaders (4%). The overwhelming majority worked in schools (87%) followed by sixth form colleges (9%) and further education colleges (2%). Other respondents described their centre as a university technical college or a private school; it is possible that other respondents were also private but did not choose to disclose this.

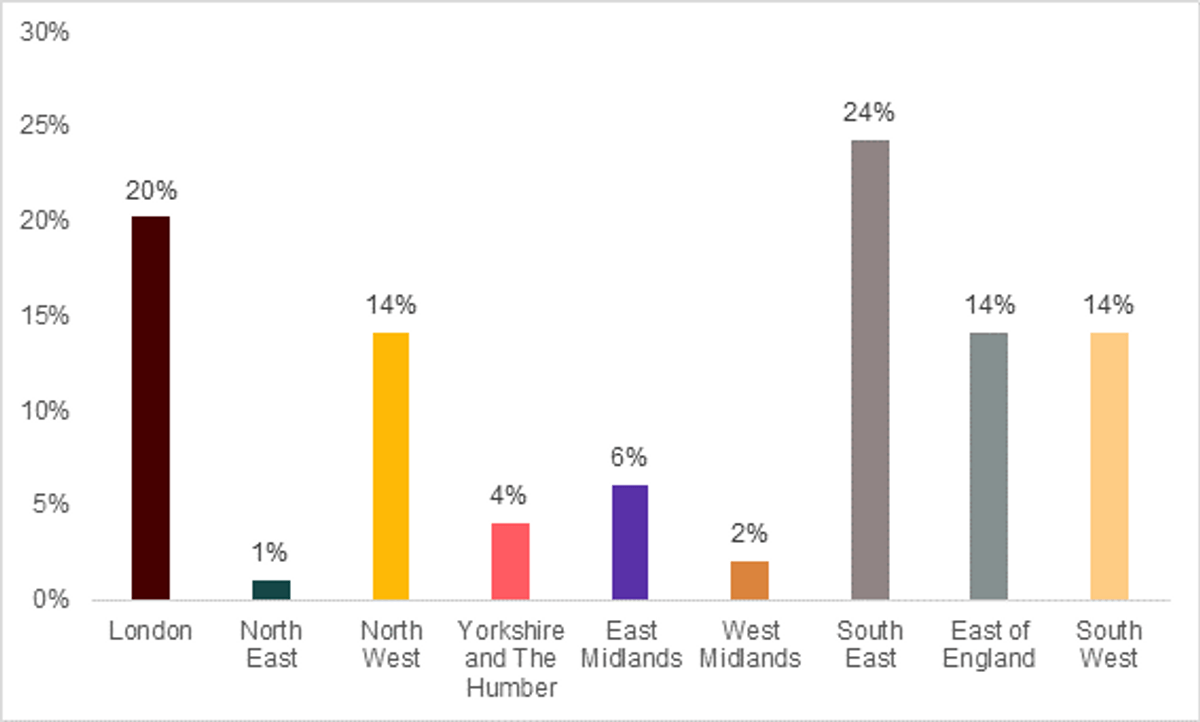

The vast majority of responses were from England, although disproportionately so from the London, the South and the North West, as the chart below shows:

Which region of the country is the centre located in?

2. Delivering On-screen assessment

2.1. Equipment

Device availability and suitability is one of the most oft-cited challenges around OSA, as is the wider IT support, internet connectivity and network reliability in place in schools.

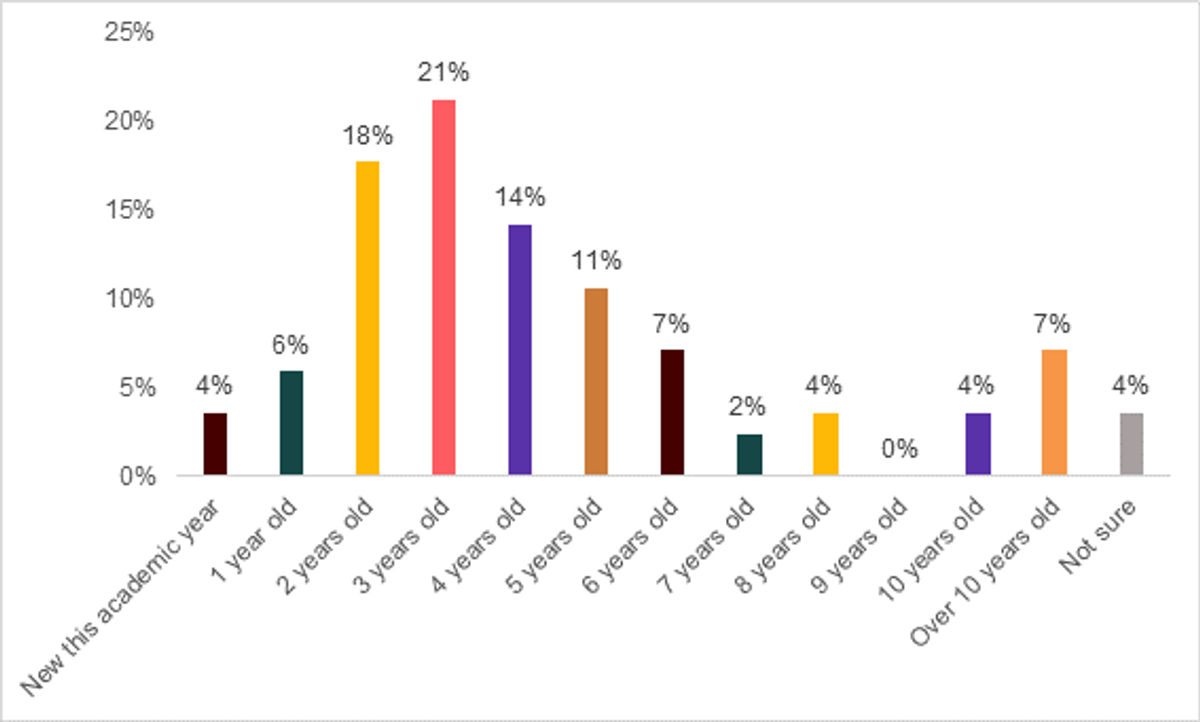

Respondents were asked about the age of their devices – results varied, with computers ranging from brand new to over ten years old:

"Roughly how old are the devices you use to deliver on-screen assessment of A-level Computer Science?"

Overall, the majority of OSAs were run on devices that had been in use for 2 to 4 years.

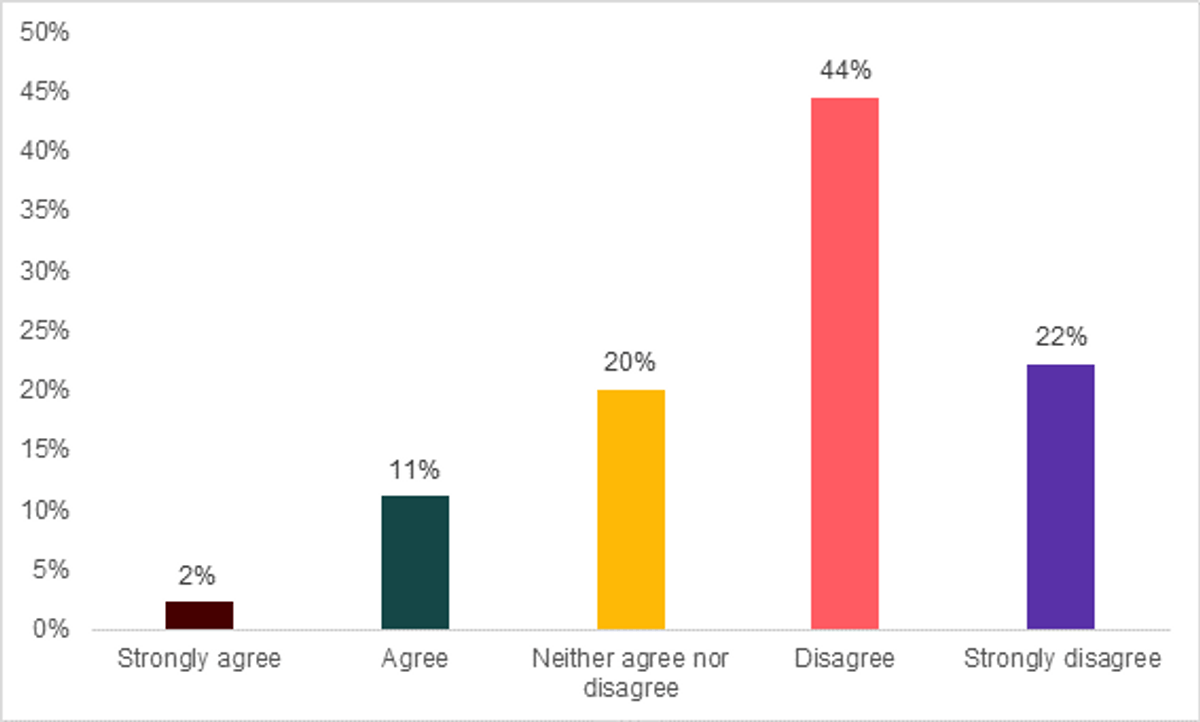

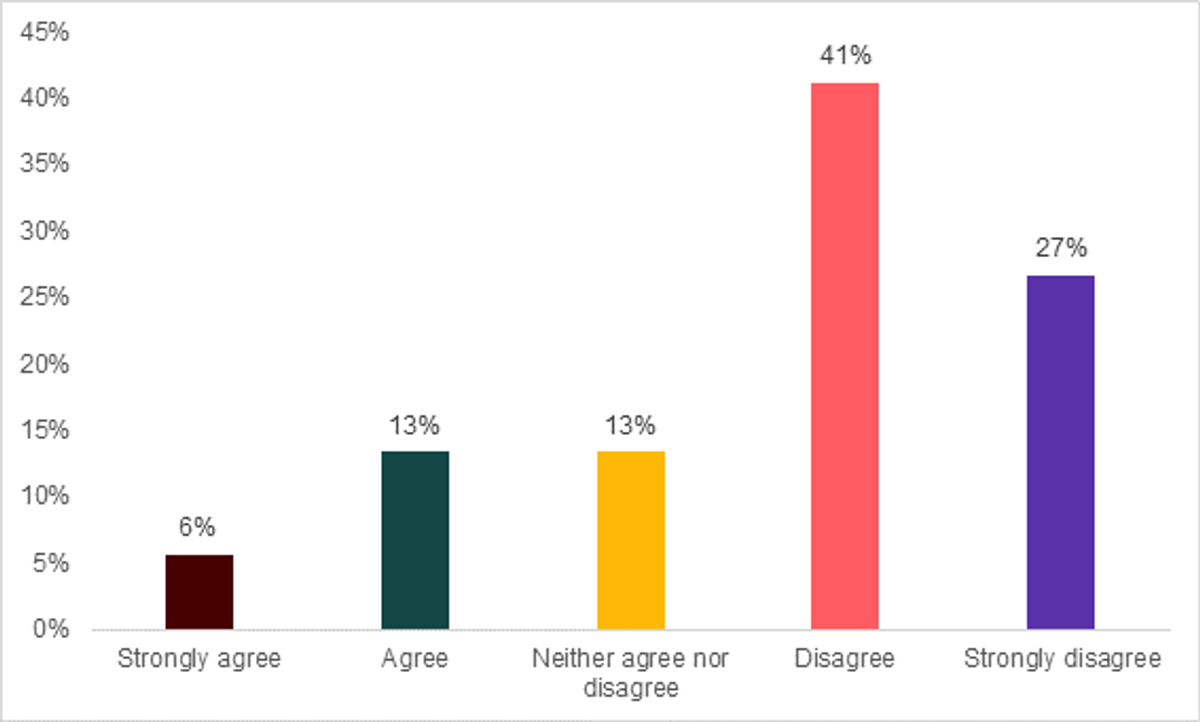

Ensuring adequate, working equipment has been an obstacle in delivering on-screen assessment of A-level Computer Science.

The majority (62%) of respondents believed that ensuring adequate and working equipment was not an obstacle in the delivery of OSA for A-level Computer Science.

Overall, the wide variations in age of devices and whether working equipment had been an obstacle suggests a varied picture in relation to IT equipment in centres – mirroring the findings of recent surveys regarding ‘EdTech’ in English schools[2].

Staff training and support has been an obstacle in delivering on-screen assessment of A-level Computer Science.

Similarly, around 6 in 10 (58%) teachers believed that staff training and support had not been an obstacle in delivery of OSA for A-level Computer Science.

2.2. Security and malpractice

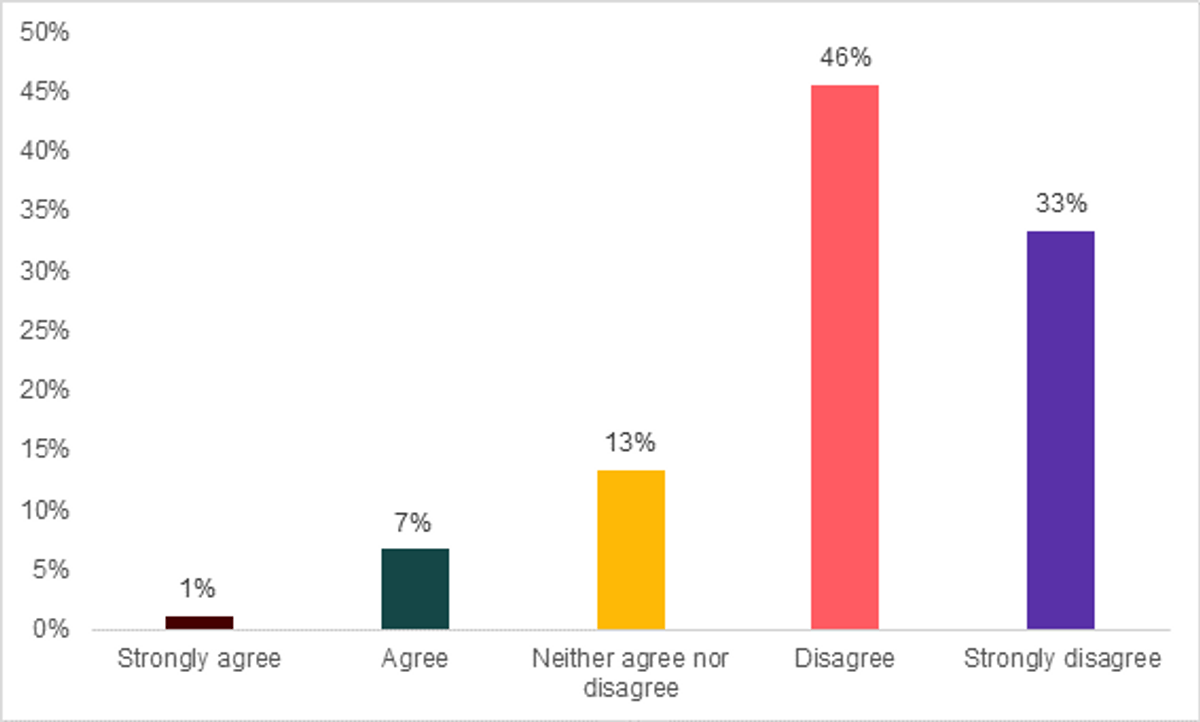

Security and malpractice are sometimes cited as areas of concern regarding greater usage of OSA in GCSEs and A-level.[3]

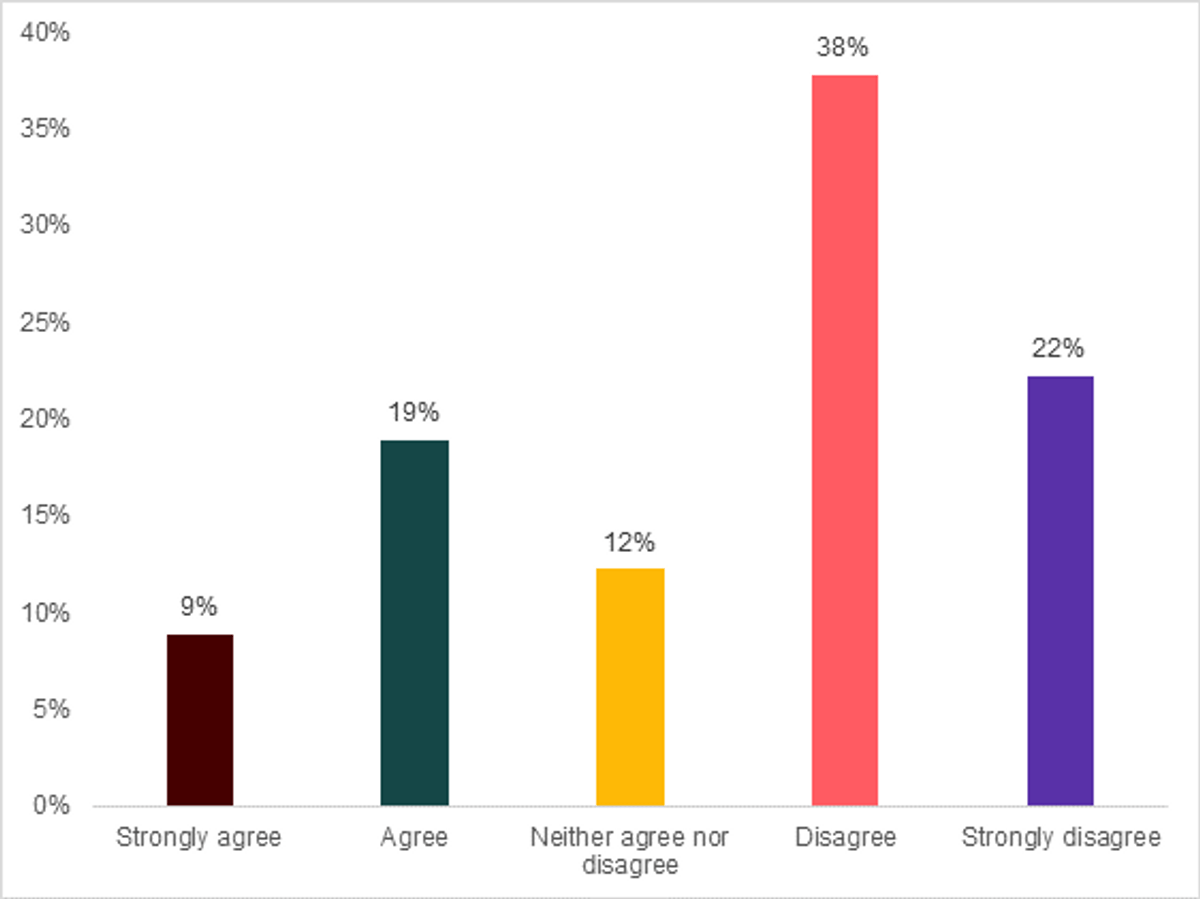

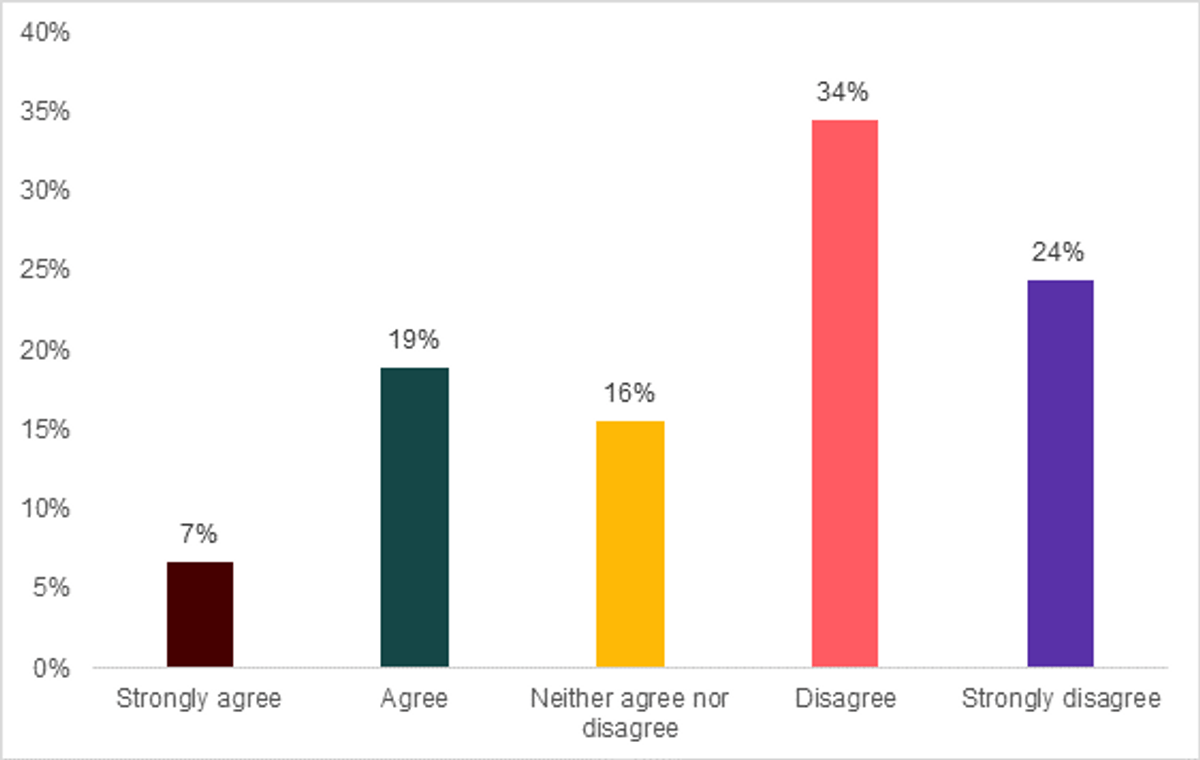

However, a minority of those surveyed agreed that they were significant obstacles in delivering OSA for A-level Computer Science, as the following charts show:

Security concerns have been an obstacle in delivering on-screen assessment of A-level Computer Science.

Malpractice concerns have been an obstacle in in delivering on-screen assessment of A-level Computer Science.

3. Student and staff experience of on-screen assessment

3.1. Student experience of OSA

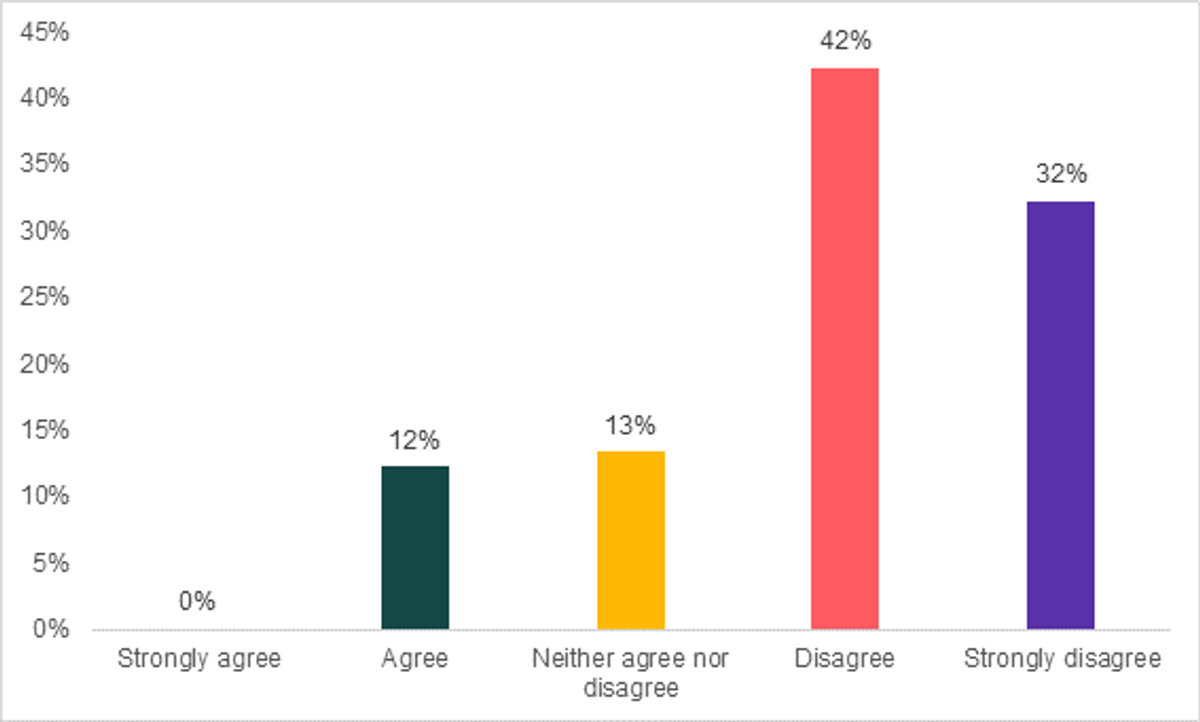

It has often been suggested that digital literacy may be a problem for students taking part in OSA. While it is tempting to assume that young people are ‘digital natives’, the reality may be that they are more familiar with a smartphone than ‘traditional’ ICT and they may therefore be disadvantaged by sitting an assessment on-screen.

Our respondents were (broadly) unconcerned with how digital literacy affects the delivery of OSAs. Around three-quarters (74%) disagreed with the suggestion that student digital literacy could present an obstacle to OSA, and no respondents strongly agreed with the suggestion:

Student digital literacy has been an obstacle in delivering on-screen assessment of A-level Computer Science.

This may be unsurprising given the subject that is being delivered using on-screen technology, which may attract students with higher levels of digital literacy.

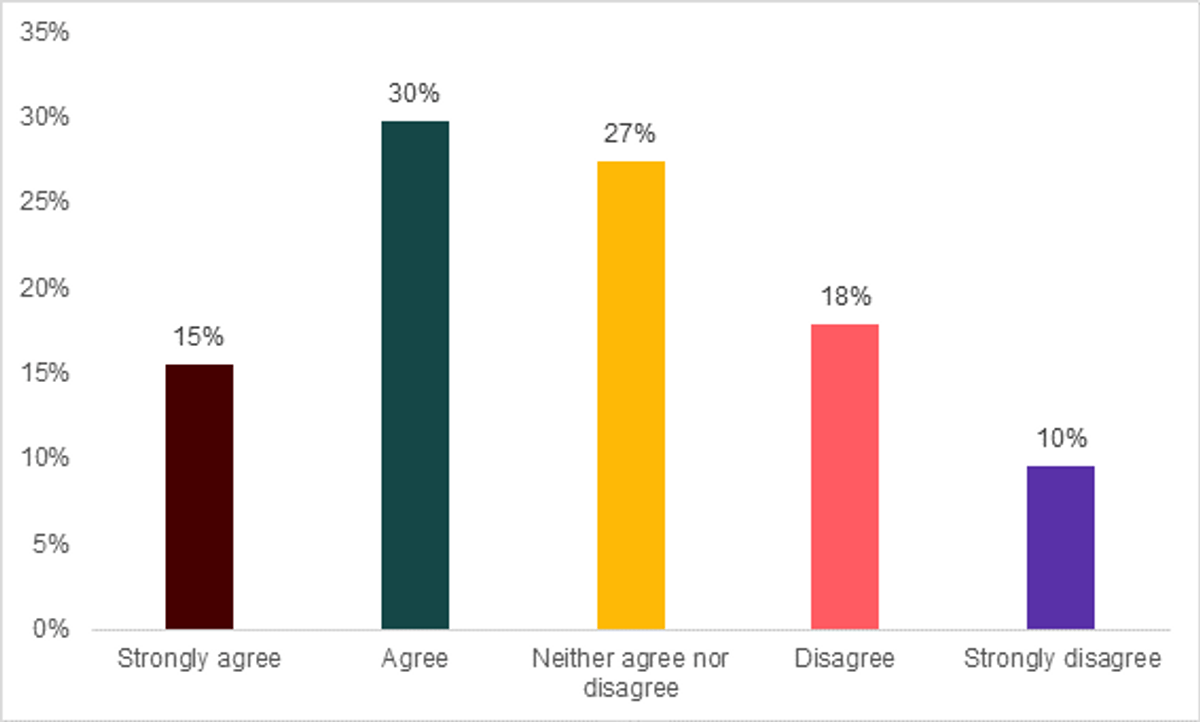

Beyond the context of OSA in A-level Computer Science, the respondents were divided as to whether most students nowadays would be more comfortable taking assessments on-screen:

Most students nowadays would be more comfortable taking on-screen assessments than using pen and paper.

3.2. Staff experience of OSA

Another concern raised in relation to OSA is the potential to increase workload for an already time-pressed school workforce.

However, our respondents were broadly positive about the overall experience of delivering OSA, with over two-thirds (68%) either disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with the suggestion that delivering OSA has been ‘difficult and challenging’:

Overall, delivering on-screen assessment of A-level Computer Science has been difficult and challenging.

These patterns also played out when respondents were asked to explain the biggest challenges in delivering OSA. Recurring themes were device availability and IT support, in addition to some difficulties with printing the student’s work, ready to send off for marking.

But while the survey questions regarding the experience of delivering an OSA (necessarily) split the experience into categories (e.g. device availability, IT support, staffing, etc.) the clearest challenge was actually a combination of these categories.

In open-text questions, respondents frequently described the challenge of having to set up a Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) and exam board compliant environment (both in the room and the digital ‘environment’), explaining to and supporting non-specialist invigilation staff, coordinating IT support and general troubleshooting. One respondent drew the challenges together neatly:

Time to check all the PCs, to set up all the special accounts, to set up and move printers. The amount of people it involves to run it (in addition to normal invigilators, [we] need several IT staff and teaching staff support to be around for [the] whole exam just in case) as well as distributing the printed copy of the exams back to students. Also shutting down the building so no other students can enter, as we have computers in open area.

Finally, when asked if using an OSA had changed the way the course was taught, responses were mixed. Attitudes were mixed (42% said no, 58% yes). Those that agreed mostly reflected on the importance of preparing students for the exam itself, which would differ from most of their other exams and GCSEs.[4]

4. On-screen assessment and other high-stake assessments

4.1. Feasibility of on-screen assessment in other qualifications

Respondents were broadly positive about the feasibility of introducing more OSA in other subject areas but were more divided as to how beneficial it would be to do so.

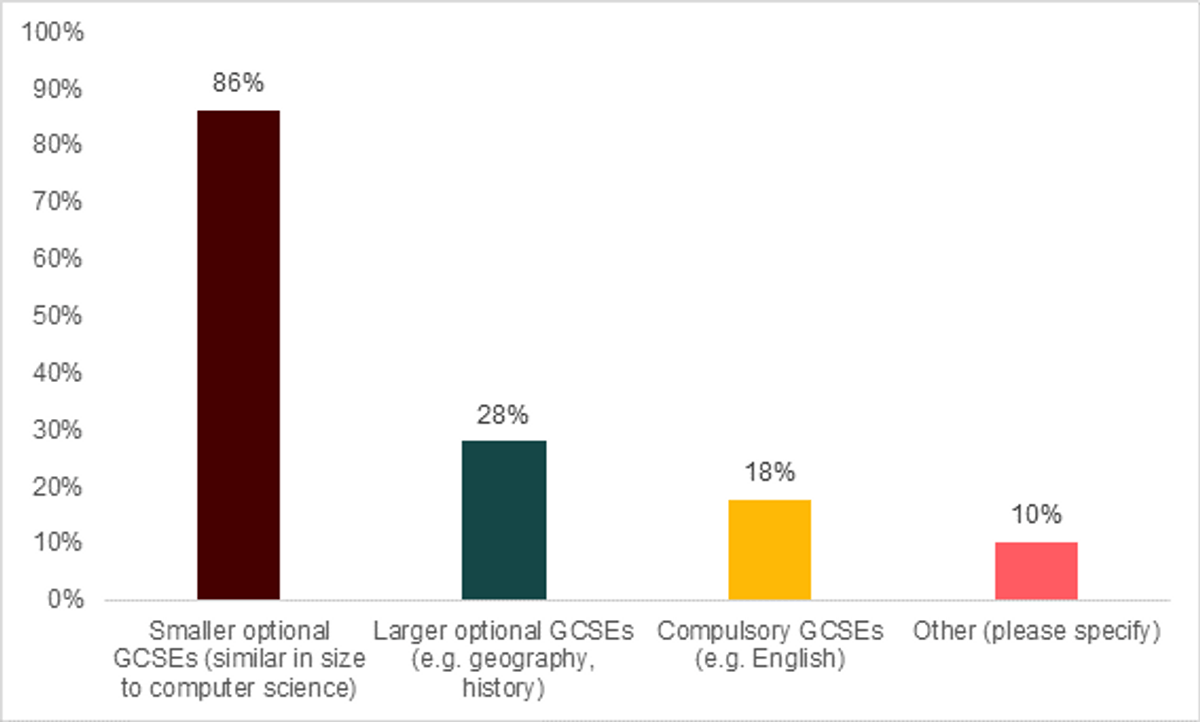

For GCSEs, respondents were confident in the feasibility of introducing OSA for smaller, optional GCSEs (86%); less so for larger or compulsory subjects:

On-screen assessment of other GCSEs should be feasible for centres to deliver: Please select all that apply

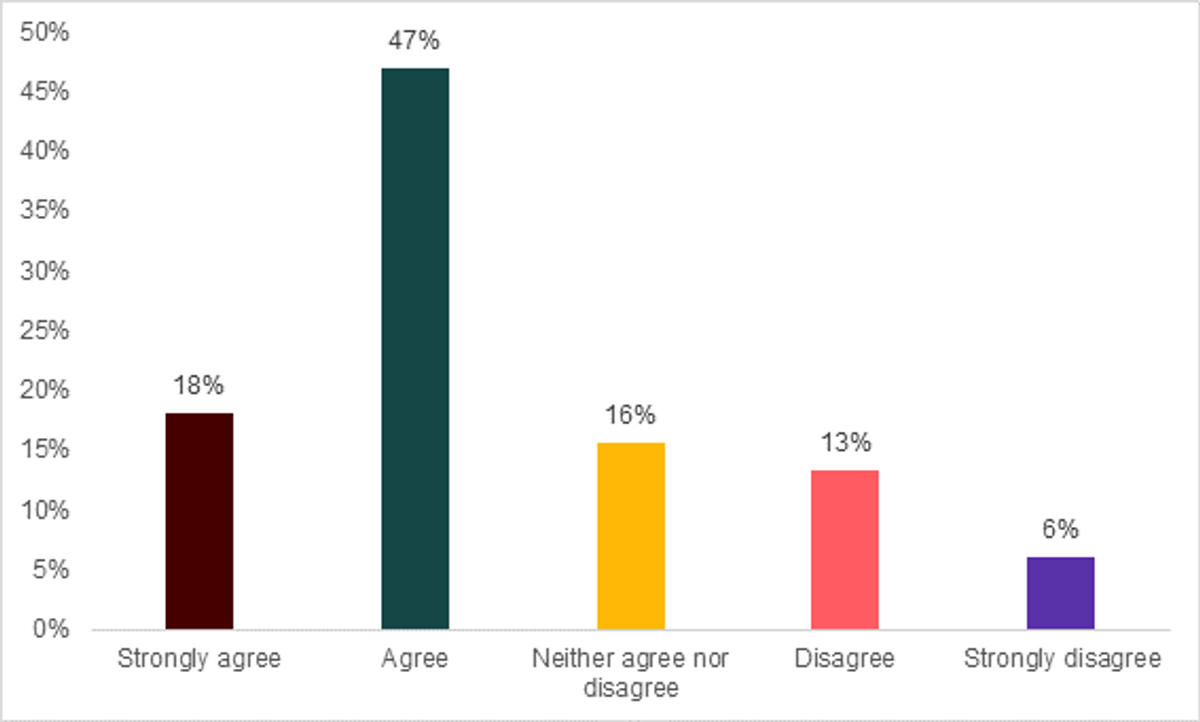

At A-level, sentiment towards introducing more OSA was also positive, with just under two-thirds agreeing or strongly agreeing that it was feasible (65%).

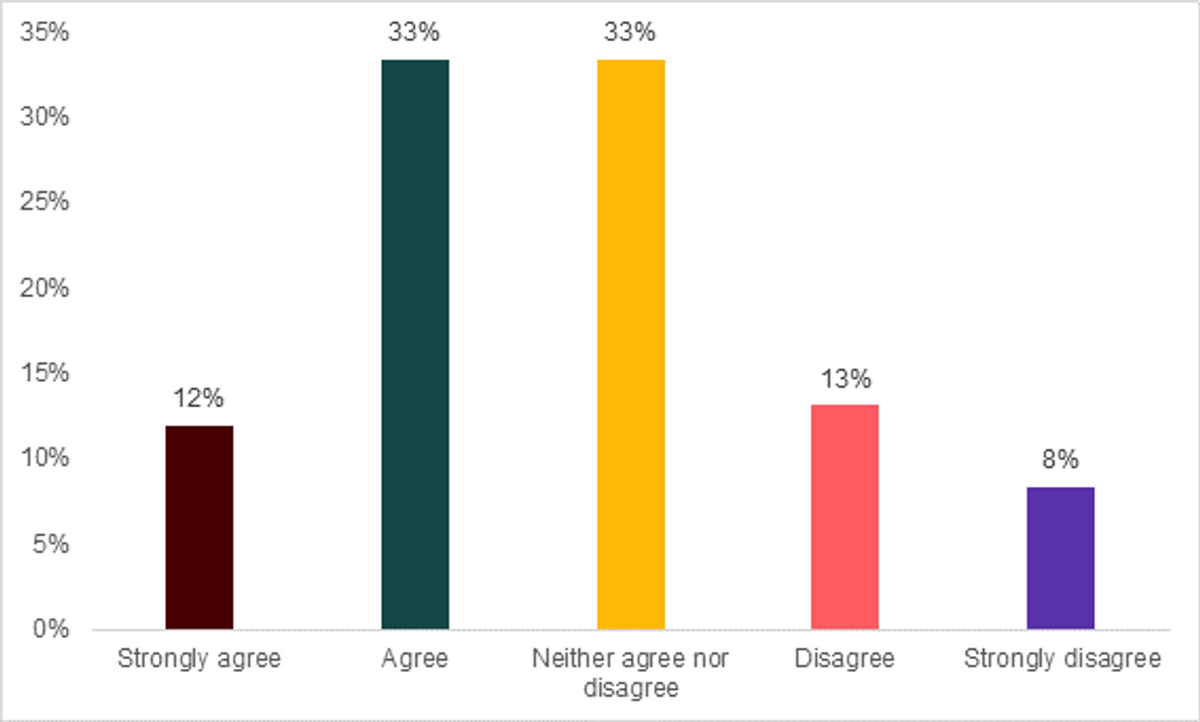

On-screen assessment of other A-levels should be feasible for centres to deliver.

4.2 Benefits of using OSA in other A-levels and GCSEs

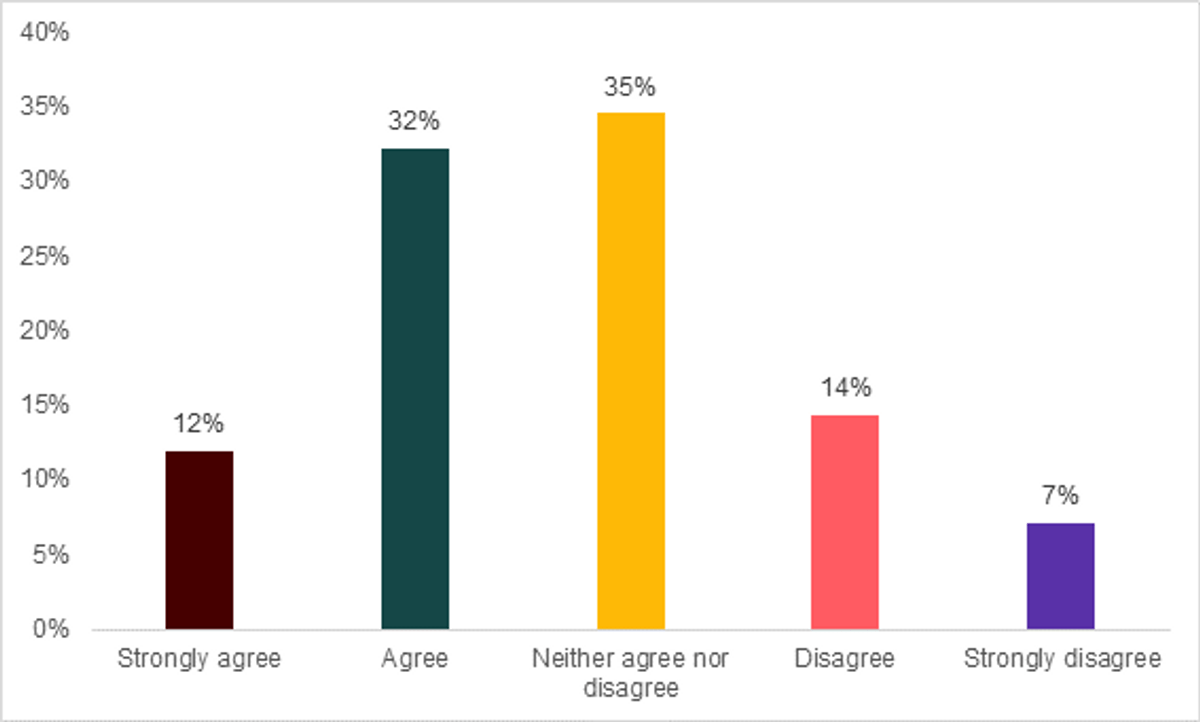

Sentiments were mixed but skewed positively as to whether further OSA should be introduced at GCSE and A-level. The balance was near identical for both questions.

Other A-level subjects would benefit from using on-screen assessments.

Other GCSE subjects would benefit from using on-screen assessments.

When asked to explain their views regarding whether more OSA in other GCSEs and A-levels would be a good idea, a range of themes emerged:

- digital literacy – student and staff

- teacher reluctance or mindset

- lack of practice time

- logistics around rooming, devices and IT support.

Digital literacy was particularly interesting since some respondents explained how even computer science students struggle with some IT basics (see above quote) while others expressed doubts around the level of general digital literacy. This uncertainty also covered staff outside the subject – teaching, support and invigilation.

Lack of practice time intersected with logistical issues, since current IT provision would not allow for all subjects to make regular use of computer spaces in the average state school.

Some respondents observed that this actually could cause problems for subjects that rely on computer facilities:

“Additional on-screen exams would create issues with the teaching of Computer Science, as it would create demand for computing facilities for exams (and mock exams) as well preparation for on-screen exams. This potentially could be disruptive to Computer Science teaching.”

This underlines the importance of device availability increasing at a proportionate rate to any proliferation of OSA.

5. Improving on-screen assessment

The survey concluded with two open questions, asking:

- What additional support would you like in order to run OSA?

- What are the most valuable messages you would pass on to government policymakers regarding the potential for using OSA for other GCSEs and A-levels?

5.1. Additional support for OSA

For the first question regarding additional support, the recurring themes in responses were:

- Investment in devices, rooming and infrastructure

- Improving digital literacy for both students and staff

- IT support, both in school and dedicated, centralised options

- Miscellaneous specification-specific improvements.

It should also be noted that the modal response was ‘none’ (or similar) i.e., teachers typically did not have any clear suggestions as to what additional support they would like to receive to run OSA.

Some respondents presented innovative solutions to the rooming and device challenge. One respondent suggested ‘sliding’ windows of assessment be introduced, which would then either make use of different questions (and potentially students).

Whilst a sizeable proportion of teachers had developed their own suggestions as to how OSA delivery could be improved, the majority did not have any clear suggestions as to what could be done to improve the process of running OSAs. However, this does not indicate that teachers believe the delivery process is faultless and highlights the complexity of the delivery process.

5.2. Messages for policymakers

The second question divided respondents as to their attitudes toward more OSA being introduced into GCSEs and A-levels, and how best to do this. The answers roughly divided along the lines of supportive with recommendations how to achieve more OSA, qualified support (i.e. limited or cautious adoption of OSA) and flat out rejection or discouragement. The reasoning is outlined and discussed below:

| View: | Reasoning, encouragement or advice to policymakers: |

| Supportive | Be prepared to fund a shift to OSA Better reflection of a digitised society work places and digitally inclined generation More inclusive form of assessment Environmental benefits |

| Qualified support | Context sensitivity Emphasis on innovation – only introducing further OSA where there is an obvious advantage Take a gradual approach Simultaneously improve student digital literacy |

| Discouraging | Sometimes unqualified rejection Importance of handwriting and other skills e.g. drawing Superiority and simplicity of paper examinations |

The above demonstrates that the reaction to this question was quite complex and difficult to characterise, without any clear consensus. Much of the above is self-explanatory and relates directly to some of the findings already described above. It is helpful to focus on some of the quotes that are either outliers or present articulate or innovative solutions to some of the problems.

For example, one respondent neatly summarised the importance of taking care to introduce OSA gradually:

Try to develop this slowly, to build confidence and to ensure that issues are dealt with before they impact on too many students and give the whole concept of OSAs a bad name.

However, comments that are less optimistic of OSA's benefits are also noteworthy:

You MUST consider a solution that does not assume candidates sitting at rows of desktop computers in an IT suite. This is no longer the model in our school; every classroom is an “IT room because students carry a computer with them, as they do a pen or pencil.”

Digital Divide is a real issue - some schools will have access to better hardware/larger screens/more resources. We need to level the playing field.

While the former makes a compelling argument and offers an attractive solution, the latter point seems consistent with the most recent findings from the EdTech survey – that device availability varies significantly across schools.

This underlines the significance of the most repeated advice in this question – the importance of funding to ensure that schools have access to devices, staff and rooms. One respondent described this particularly clearly, while also outlining the long-term benefits:

There is a good financial and environmental incentive for OSAs, as well as aligning students with a more modern era of working. It requires initial investment to [see] longer term gains but would also speed up the process of getting exam answers into examiner hands.

Finally, one respondent argued that the rationale for OSA should focus on quality of assessment, not just reducing the burden of exams:

OSA should only be used where there is an advantage to students - to improve the quality of assessment and not to reduce the administration of the exam.

The case can therefore be made that OSA is highly relevant, and desirable, in subjects such as Computer Science; complimenting students' expectations as to how they would be assessed on a specification focused on digital skills.

6. Conclusion

The findings of this survey are important in that they represent views from teachers who have experience of delivering OSA over a number of years. While interest in OSA is on the rise, there is relatively little attention paid to the OSA that already exists in the English exam system, and how experienced professionals view what is available.

Several points can be made with confidence based on this survey:

- The majority of our respondents do not view internet connectivity or the risk of malpractice as a problem – although this may be a reflection of this specific OSA; different designs may elicit different reactions

- Training and equipment is a delivery concern for only around a quarter of teachers

- Computer science teachers believe that it is entirely feasible to offer more OSA at GCSE (smaller subjects) and A-level.

Respondents felt it is feasible to deliver more OSA in GCSEs and A-levels, but they were divided on whether this was actually a good idea in practice. While there is an array of justifications explored here, it does seem that many of the varied sentiments stem from equally varied practical experiences of delivering OSA, and that funding to help achieve a more consistent process across the country could prove a helpful step for any policymaker interested in supporting both ongoing and future efforts to implement OSA.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/education-secretary-delivers-speech-at-bett-show

[2] CooperGibson Research. (2021). Education Technology (EdTech) Survey 2020-21: Research report. Department for Education. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/996470/Education_Technology__EdTech__Survey_2020-21__1_.pdf

[3] Ofqual. (2020). Online and on-screen assessment in high stakes, sessional qualifications. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/943382/Barriers_to_online_111220.pdf

[4] Not all exam boards currently offer on-screen examinations for computer science at GCSE.