Assessment

Stepping Stone: the future of the EBacc and student progression

Over a decade since its inception, AQi explores whether the EBacc curriculum is the right stepping stone to post-16 study and training for pupils in England.

Executive summary

Curriculum debate in England often focuses on Key Stage 4: the GCSE curriculum young people study aged 14-16 before they diverge into academic, vocational and technical post-16 education pathways.

The government’s ambition is for the vast majority of students in England to enter for a set of core, academic GCSEs known as the EBacc, which it believes represents the best stepping stone for keeping young people’s post-16 options open to further study and future careers.

To inform debate around the EBacc, this report brings together analysis and key evidence.

The EBacc: An Overview

The government wants 75% of students in England to enter for the EBacc by 2022 and 90% by 2025. To encourage entries, the EBacc forms the basis of two school performance measures.

The EBacc seeks to break the historic link between GCSE choices and pupils' background, which saw some students make choices aged 14 that narrowed their post-16 options. Multiple government Ministers have highlighted the role of the EBacc in advancing social mobility.

At launch, the government linked the GCSE subjects in the EBacc to the Russell Group’s list of so-called ‘facilitating subjects’. However, in 2019, the Russell Group set aside this list.

The EBacc’s Impact: Student choices and pathways

The proportion of students in England entering for the full EBacc has flatlined at 40% since 2014. However, there has been a significant shift toward EBacc GCSE subjects and by 2019, over 85% of students entered for four or more of the five EBacc pillars.

There appears to have been a modest increase in the proportion of Level 3 students entering for A-levels and entering for EBacc subjects at A-level. However, while some EBacc subjects have seen a growth in A-level entries, some have declined, indicating the influence of other factors on subject choices. Indeed, some subjects have seen a growth in entries at A-level over the last decade, despite their exclusion from the EBacc.

It is not possible to draw conclusions regarding the impact of the EBacc on (disadvantaged) students attending (highly selective) universities, owing to the multiple factors that determine such decisions at an individual and cohort level.

Evaluating the EBacc

Is the EBacc the best stepping stone for progression to post-16 education and future careers?

EBacc GCSEs do keep young people’s options open given – unlike many other Level 2 qualifications – they are accepted and used for entry to the widest range of Level 3 subjects and progression routes, including A-levels, vocational and technical qualifications. Some students are likely to make better choices and have better outcomes because of the EBacc.

However, the EBacc may crowd out a more diverse curriculum and may close some options for students, eg creative arts. EBacc subjects may lead to lower levels of educational engagement and motivation for some, and there is evidence some students may achieve lower overall GCSE grades because of entering for the EBacc, thereby narrowing their options.

In short, there are both pros and cons to the EBacc as a stepping stone to post-16 education and training. This is reflected in the views of around 4,000 secondary school teachers who were surveyed for the purposes of this report, which found opinion was split three ways between supporting, opposing and being ambivalent toward key tenets of the EBacc policy.

A Different Stepping Stone? EBacc options for policymakers

Would a different EBacc provide a better stepping stone to post-16 education and careers?

Policymakers have several options. These include widening the EBacc to give students greater flexibility while still influencing subject choices, or introducing multiple EBacc suites geared toward technical, art and science routes in order to allow students to choose a pathway more aligned to their interests aged 14. Policymakers could also simply remove the EBacc from school performance measures and instead focus on using enhanced information and advice to guide GCSE subject choices.

However, as with the EBacc in its current form, each option has clear pros and cons.

Conclusion

Students would be best served if debate on the EBacc focused on whether it provides the best stepping stone to post-16 education and training relative to other options.

Judging between different options requires careful consideration and evaluation. For example, the extent to which widening the EBacc might improve levels of student interest, engagement and motivation, but risk students making choices that narrow their post-16 options as a result.

This is something that can be evaluated, but relevant evidence is simply not available at present, despite the data generated by hundreds of thousands of students taking GCSEs each year.

Indeed, while the choice of subjects in the EBacc do keep young people’s options open, there is insufficient evidence to say whether the EBacc policy overall has achieved this aim, has done so equitably for all types of student, and whether the trade-offs involved are justified.

More research is required, for example, to investigate:

- Relative levels of motivation, enjoyment and education at the end of Key Stage 4 among different types of student who enter for three, four and five EBacc pillars, and different subject combinations

- The attainment and other outcomes of students in post-16 vocational and technical pathways who enter for different EBacc/non-EBacc subject combinations.

The government should also consider adopting a data-driven approach to setting the EBacc subjects. For example, student-level pathways could be analysed to identify which GCSE subject combination is associated with the most diverse progression pathways.

1. Introduction

Debate about what young people should learn during their education is common throughout the world.

In England, such debate is particularly intense in relation to Key Stage 4, i.e. the GCSE curriculum young people study aged 14-16 before they diverge into academic, vocational and technical post-16 education pathways.

The government’s ambition is for the vast majority of students in England to enter for a set of academic GCSEs known as the EBacc, and it has been incorporated into school performance measures for this reason. The EBacc seeks to break the link between student background and GCSE choices, and the government believes the EBacc represents the best stepping stone for keeping young people’s options open to further study and future careers.

However, more than a decade since its’ introduction, views of the EBacc remain mixed. For example, a survey of state secondary school teachers undertaken for this report - and described in subsequent sections – found highly mixed views of the purpose and merits of the EBacc.

Advocates of the EBacc have argued that it promotes social mobility by encouraging young people from every background to access those academic subjects that are the stepping stone to high-status universities and careers.

Critics of the EBacc argue that it is too focused on academic subjects, forces some students to do GCSEs they have little interest in or use for, and the choice of subjects in the EBacc lacks a clear rationale.

Such criticisms have become louder in the wake of the government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda, and education Ministers have recently highlighted the need to “have balance around how we engage as many people as possible while aiming for high levels of attainment.”[1]

To inform debate around the EBacc, this report brings together analysis and key evidence to evaluate whether it is the best stepping stone for progression to post-16 study and training.

Section 2 of the report provides an overview of the EBacc, its purpose and its position relative to school performance measures.

In Section 3, the impact of the EBacc over the last decade is explored in relation to GCSE entry choices, post-16 progression pathways, A-level subject choices and progression to Higher Education.

Section 4 explores the key pros and cons of the EBacc policy that have been identified in debate, for example, in relation to social mobility and academic achievement.

In Section 5, policy options for reforming the EBacc are identified and evaluated, for example, widening the range of GCSE subjects it covers.

Section 6 concludes the report with key recommendations for policymakers.

2. The EBacc: An overview

Key points:

- The EBacc is a suite of academic GCSE subjects which the government wants 75% of students in England to enter for by 2022 and 90% by 2025.

- The purpose of the EBacc is to ensure that as a stepping stone to post-16 education and training, the GCSEs students enter for provide a wide range of post-16 study and progression options.

- At launch, the government linked the GCSE subjects in the EBacc to the Russell Group’s list of so-called ‘facilitating subjects’. However, in 2019, the Russell Group set aside this list.

2.1. What is the EBacc?

There are around 50 different GCSE subjects offered in the English education system, ranging from Biology and German to Astronomy and Film Studies.[2]

| Ancient history Arabic Astronomy Bengali Biblical Hebrew Biology Business Citizenship Studies Classical Civilisation Classical Greek Combined Science Computer Science Chemistry Chinese (spoken Mandarin/Cantonese) Dance Design and technology Drama Economics | Electronics Engineering English Language English Literature Film Studies Food preparation and nutrition French Geography Geology German Greek Gujarati History Italian Japanese Latin | Mathematics Media Studies Modern Hebrew Music Panjabi Physical Education Persian Physics Polish Portugese Psychology Religious Studies Russian Sociology Spanish Statistics Turkish Urdu |

The English Baccalaureate – widely known as the ‘EBacc’ – is a suite of academic GCSE subjects which the government desires the majority of students to study and enter for.

The government has stated that its ambition is to see 75% of students in England studying an EBacc subject combination at GCSE by 2022 and 90% by 2025.[3]

However, besides maths, English and the sciences, the government has limited direct control over the GCSEs that students enter for and what GCSEs schools offer. In order to encourage entries to the EBacc, the government has therefore made it the basis of two school performance measures. These are:

- the percentage of pupils who enter for the EBacc

- the English Baccalaureate Average Point Score (EBacc APS).

The EBacc requires students to take one subject in each of five academic ‘pillars’, although the precise requirements vary for each pillar.[4]

| Pillar | Subjects | Requirements |

| English | English Literature, English Language | To count towards the English part of the EBacc, pupils need to take both English literature and English language GCSE exams |

| Mathematics | Mathematics | |

| Science | Double Science, Triple Science, Computer Science | Students need to take one of the following options: 1) GCSE combined science – pupils take 2 GCSEs that cover the 3 main sciences, biology, chemistry and physics 2) 3 single sciences at GCSE – pupils choose 3 subjects from biology, chemistry, physics and computer science |

| Humanities | History, Geography | |

| Languages | French, Spanish, German, (Mandarin) Chinese, Biblical Hebrew, Persian, Turkish, Portugese, Classical Greek, Latin, Japanese, Urdu, Russian, Dutch, Panjabi, Bengali, Polish | Any ancient or modern foreign language GCSE counts towards the languages components of the EBacc |

Entering the full EBacc requires students to take a minimum of seven GCSEs. Ofqual analysis of 2021 GCSE entry data found that the average (mean) number of GCSEs entered for was 7.85, compared to 8.09 in 2018.[5]

This suggests that, while entering for a full suite of EBacc GCSEs does not prevent students from entering for additional, non-EBacc subjects, for most this will comprise one or two additional subjects at most.

In 2016, the government introduced additional school performance measures - ‘Attainment 8’ and ‘Progress 8’ - which also draw on the EBacc. In particular, Attainment 8 measures pupils’ attainment across eight qualifications including:[6]

- Maths (double weighted) and English (double weighted, if both English language and English literature are sat)

- Three qualifications that count in the English Baccalaureate (EBacc) measures

- Qualifications that can be GCSE qualifications (including EBacc subjects) or technical awards from the DfE approved list Performance tables: technical and vocational qualifications.

2.2. What is the purpose of the EBacc?

The Department for Education (DfE) defines the EBacc as a set of GCSE subjects that “keeps young people’s options open for further study and future careers.”[7]

Put another way, the purpose of the EBacc is to ensure that as a stepping stone to post-16 education and training, the set of subjects Key Stage 4 students enter for provides them with wide a range of post-16 study and progression options. In particular, the EBacc has been designed to ensure student decisions are not accepted onto selective universities due to the subjects that they studied at 14-18.

The creation of the EBacc and its inclusion in school performance measures therefore seeks to influence the decisions of:

- Students in choosing GCSE subjects

- Centres in determining which GCSE subjects to offer.

2.3. Why does the government want to keep young people’s options open?

Prior to the introduction of the EBacc, many stakeholders were concerned that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds were choosing, or being encouraged to choose, less academic GCSE subjects, which ultimately hindered their progression to high-status universities and careers. In short, their GCSE choices were narrowing their future options.

Various studies have underpinned such concerns. A 2010 DfE report studying the behavioural factors behind subject uptake found that students’ subject choices were based on a combination of biased reasoning and imperfect information on what subjects would improve their post-16 study options.[8]

In 2012, a DfE study identified a correlation between schools with high proportion of children qualifying for free school meals (FSM) and low entries into the EBacc suite of subjects, particularly in the North of England.[9]

Research published in 2018 examined the GCSE choices of those born in 1989-90.[10]It found that “prior attainment is positively and significantly associated with how academically demanding the subjects selected are. Controlling for prior attainment, the differentials due to socioeconomic factors are reduced, but significant differences remain.”[11] The research also found that ethnic and gender differences in subject choices are not accounted for by prior attainment.

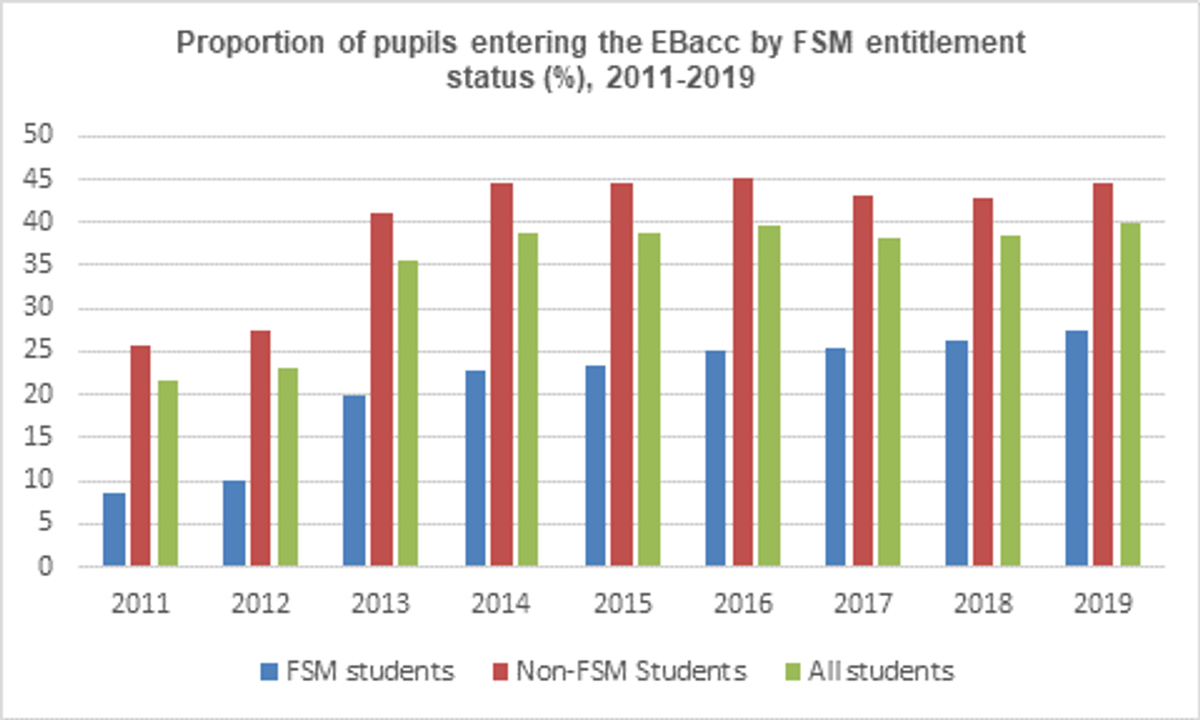

More widely, stakeholder concern regarding the effect that socioeconomic background has on GCSE subject choices is underpinned by the fact that – as explored below – students entitled to Free School Meals (FSM) continue to be less likely to enter for the EBacc long after its incorporation into school performance measures. In short, even after a decade of the EBacc, it appears that socioeconomic background influences GCSE subject choices.

As a policy intervention, the introduction of the EBacc therefore seeks to tackle directly the complex range - and interaction - of influences and drivers that historically shaped student decisions at age 14 regarding GCSE subject choices. These may take many forms, and in many cases, revolve around a trade-off between subjects with a more certain reward and academically rigorous subjects that enable students to fulfil their academic potential. For many students, GCSE subject decisions are informed by factors specific to the individual, such as family networks, accessibility to careers guidance and personal feelings and experiences with different subjects during their formative school years.[12]

As a policy to directly address socioeconomic differences among students which historically materialised in their subject choices at GCSE, the EBacc represents an important pillar of the government’s use of education to promote social mobility.

Indeed, since its launch in 2010, various Ministers have highlighted the role of the EBacc in ensuring attainment, rather than personal upbringing, determines student outcomes. For example:

To become a great meritocracy, we need an education system which ensures that everyone has a fair chance to go as far as their talent and hard work will allow. We need to remove the barriers that stop people from being the best they can be, and ensure that all children are given the same chances through education to succeed... An important part of this will be ensuring that children have the opportunity to study the core academic subjects at GCSE - English, maths, science, history or geography and a language - the English Baccalaureate (EBacc). [13]

(Justine Greening, July 2017)

In secondary schools, our more rigorous academic curriculum and qualifications support social mobility by giving disadvantaged children the knowledge they need to have the same careers and life opportunities as their peers. [14]

(Nick Gibb, March 2019)

"[The EBacc was]…introduced to ensure that all children have the opportunity to be taught the type of academic curriculum too often restricted to pupils from more privileged backgrounds. [15]

(Nick Gibb, July 2021)

2.4. How was the choice of EBacc subjects determined?

At the time of its launch, the government explicitly linked the choice of GCSE subjects included in the EBacc with the list of so-called ‘facilitating subjects’ published by the Russell Group, a university membership body. For example:

The Russell Group has been quite clear about the core GCSE and A-level subjects which equips students best for the most competitive courses - English; maths; the three sciences; geography; history; classical and modern languages.

So the E-Bacc is designed to open up those same subjects to tens of thousands of state pupils currently denied the opportunity.[16]

(Nick Gibb, June 2011)

However, in 2019, the Russell Group set aside the list of facilitating subjects in favour of an interactive website providing students with information that enables them to test out different combinations of subjects based on their interests to find out the degrees that may be open to them.[17]

In fact, since its introduction, multiple stakeholders have challenged the choice of GCSE subjects comprising the EBacc, including in relation to effect on attending university. For example, a 2018 study using data on young people aged 14 in 2004-5 found that large raw differences in the probability of university attendance by subjects studied. However, once differences in the characteristics of individuals who study such subjects are taken into account, the remaining differences are positive but small, observing a 3 percentage point increase in the likelihood of university attendance.[18]

The choice of GCSE subjects in the EBacc has also been influenced by a growing volume of evidence published in recent years exploring how subject choices influence income and employability. Such evidence highlighted how different undergraduate degree courses are associated with variations in lifetime earnings. For example, the lower earnings associated with creative arts subjects.[19]

In a similar vein, research published by DfE examined the link between GCSE subjects and lifetime earnings, albeit using very historic data.[20]While a number of caveats around the findings should be noted, the research found that the GCSE subject taken by those whose earnings are largest is Triple Science - ie biology, chemistry and physics. However, as the report highlights, this link must be contextualized by the personal characteristics of the pupils who studied these subjects, who were typically high-attaining at KS2, acquired more GCSE qualifications and comprised the lowest percentage of FSM-eligible pupils compared to other GCSE subjects.[21]

In its focus on core, academic subjects, and ensuring as many young people have access to the knowledge and skills they provide, the introduction of the EBacc as a curriculum policy can also be seen as being influenced by the American theorist and educator, E. D. Hirsch, who has been repeatedly cited by DfE Ministers during the last decade.[22] Across a number of publications, Hirsch argues that flawed approaches to curriculum and learning have culminated in a “knowledge-deficit” among students in many western countries. Hirsch argues those students who master a select number of fundamental capabilities - such as understanding core literary texts - are more likely to flourish in their studies.[23]

3. The EBacc's Impact: Student choices and pathways

Key points:

- The proportion of students in England entering for the full EBacc has flatlined at 40% since 2014. However, there has been a significant shift toward EBacc GCSE subjects and by 2019, over 85% of students were entered for four or more of the five EBacc pillars.

- There appears to have been a modest increase in the proportion of Level 3 students entering for A-levels and entering for EBacc subjects at A-level. However, while some EBacc subjects have seen a growth in corresponding A-level entries some have declined, indicating the influence of other factors. Indeed, some non-EBacc subjects have seen a growth in entries at A-level over the last decade, despite their exclusion from the EBacc.

- It is not possible to draw conclusions regarding the impact of the EBacc on (disadvantaged) students attending (highly selective) universities, owing to the multiple factors that determine such decisions at an individual and cohort level.

3.1. Introduction

The government launched the EBacc and incorporated it into school performance measures in order to influence student GCSE subject choices – particularly disadvantaged students - and to keep young people’s post-16 options open.

What impact has the EBacc had on student choices and pathways over the last decade?

3.2. KS4 entries into EBacc and non-EBacc subjects

Even before the EBacc was introduced into school performance measures, those GCSE subjects in the EBacc were typically among the most popular. GCSE maths and English, which comprise two of the five EBacc ‘pillars’ were and remain compulsory.

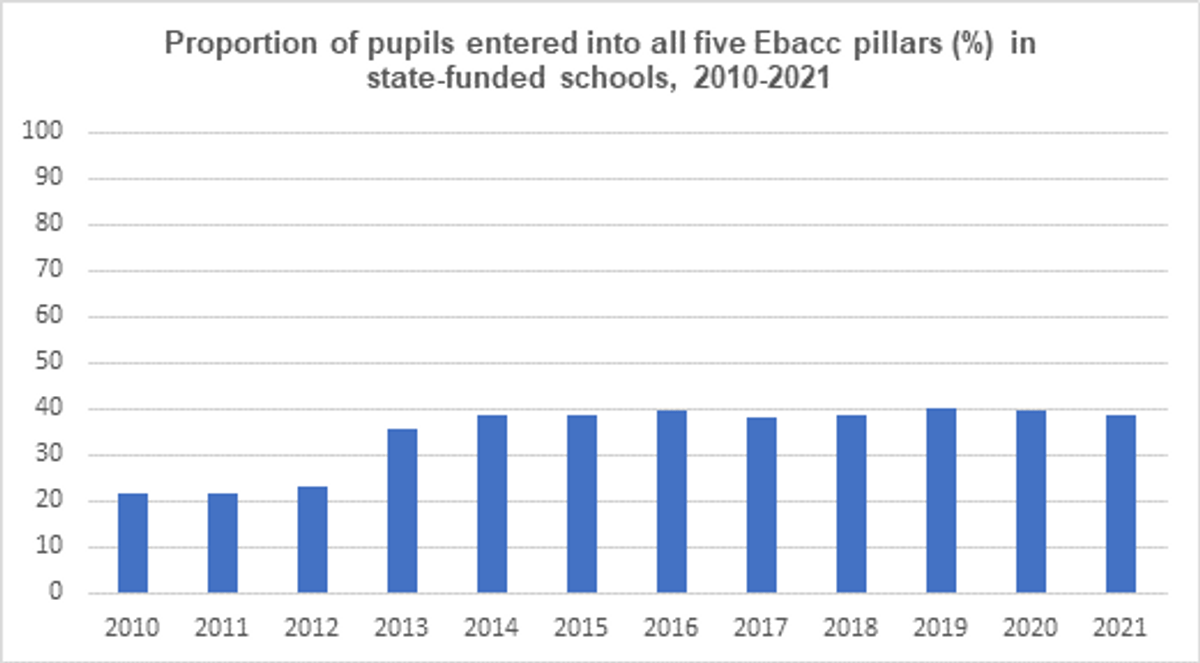

Historic entry data show that the proportion of students in England entering for the full EBacc suite increased from around one in five at its launch to around two in five by 2014. Since then, the proportion has remained largely unchanged:[24]

Source: Education Statistics Service.

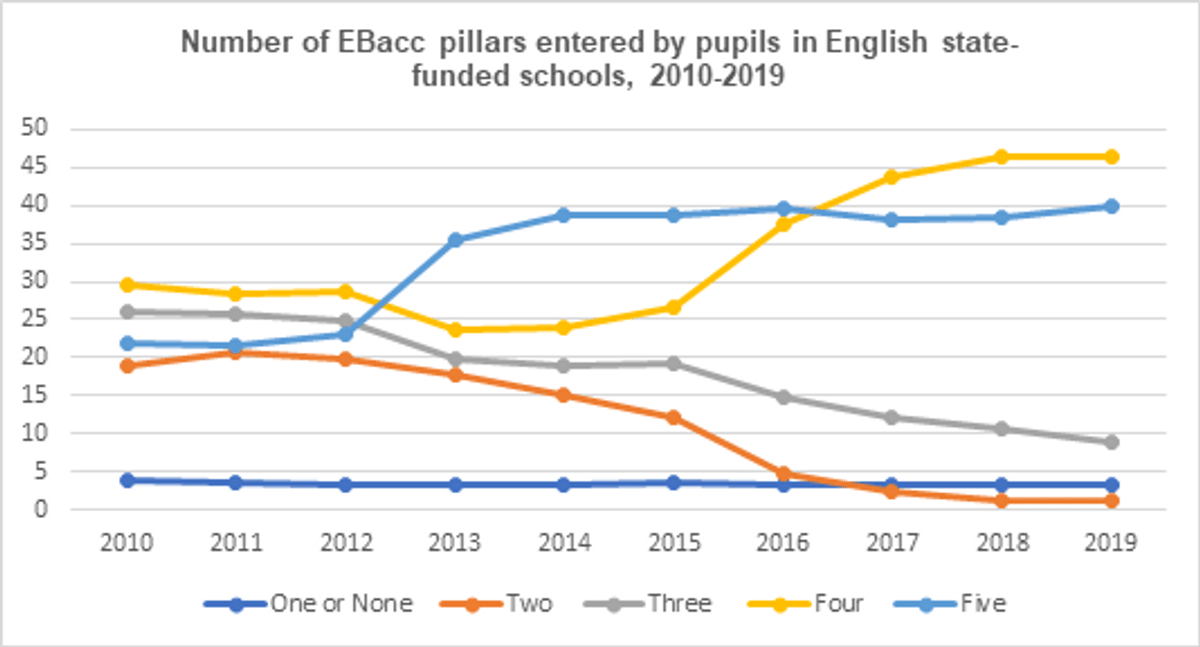

However, despite entries to the full EBacc remaining flat since 2014, there has been continued growth in the proportion of students who enter for the majority, but not all, of the EBacc pillars, as the following chart shows:

By 2019, over 85% of students were entered for four or more of the five EBacc pillars.

The proportion of all GCSE entries that were EBacc subjects has risen during the last five years from 76% in 2017 to over four fifths (82%) in 2021, according to Ofqual data:[25]

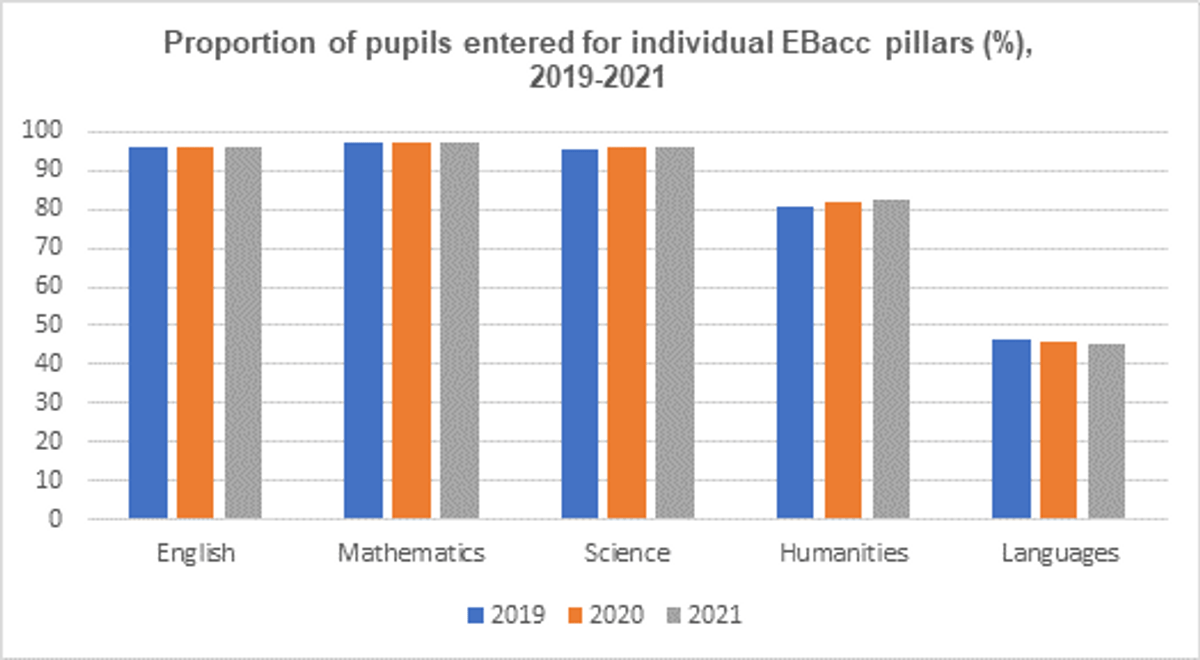

Given the compulsory nature of maths, English and science in the Key Stage 4 curriculum, it is not surprising that the EBacc pillars students are least likely to enter for Humanities and- in particular- languages.

Source: Education Statistics Service.

Indeed, among students who had entered for four of the five EBacc pillar requirements in recent years; for example, in 2018, the vast majority of pupils that failed to meet the EBacc's subject criteria (83.9%) had not enrolled for a language GCSE.[26]

This is consistent with GCSE subject entries data, which shows that language GCSE entries have steadily declined after peaking at 50% in 2014.[27]

Overall, GCSE subject entry patterns in the decade after its introduction suggest the EBacc has had a significant impact on student decisions. However, issues pertaining to language GCSEs in particular have prevented more substantial progress toward the government’s ambition of 75% of students entering for the full EBacc.

| A number of factors may explain the relatively low entries for GCSE languages. The decline may reflect the perceived usefulness or the relative difficulty of these subjects. Uptake has also been linked to subject provision and systemic issues in the supply and demand of MFL teachers, where an additional 3,400 languages teachers were needed to deliver the EBacc to all students based on 2017 figures. Source: Education Data Lab (2017) Revisiting how many language teachers we need to deliver the EBacc |

Given the social mobility aims of the EBacc policy, it is also important to note that since its introduction, there has been an increase in the proportion of students entitled to Free School Meals (FSM) entering for the full EBacc. However, as the following chart shows, while entries to the full EBacc among this group rose from around 10% when the EBacc was launched to around 30% by the end of the decade, this was still significantly lower than non-FSM students:

Source: DfE (2019) Key Stage 4 performance

3.3. 16-18 progression pathways

The purpose of the EBacc is to encourage students to enter for a defined set of GCSE subjects that the government believes will keep their options open for further study and future careers.

As such, while the target of the government’s EBacc policy is GCSE entry patterns, the desired outcomes from the policy relate to post-16 student choices and pathways.

Many factors besides GCSE subject choices and the EBacc will influence post-16 progression pathways. However, in exploring the impact of the EBacc, it is nevertheless worthwhile to review what changes in 16-18 subject choices and progression pathways among students in England can be observed since its introduction.

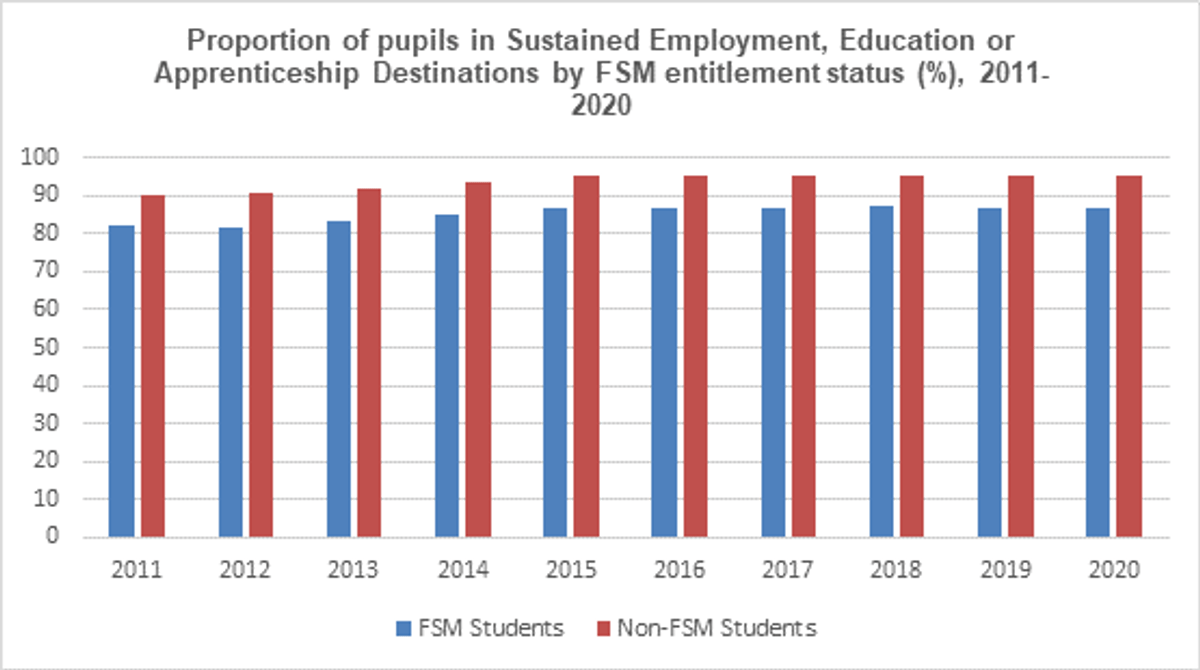

The following chart shows there has been negligible change in the proportion of those aged 16-18 in England who have remained in sustained education, apprenticeship or employment since the EBacc was introduced.

Source: Education Statistics Service.

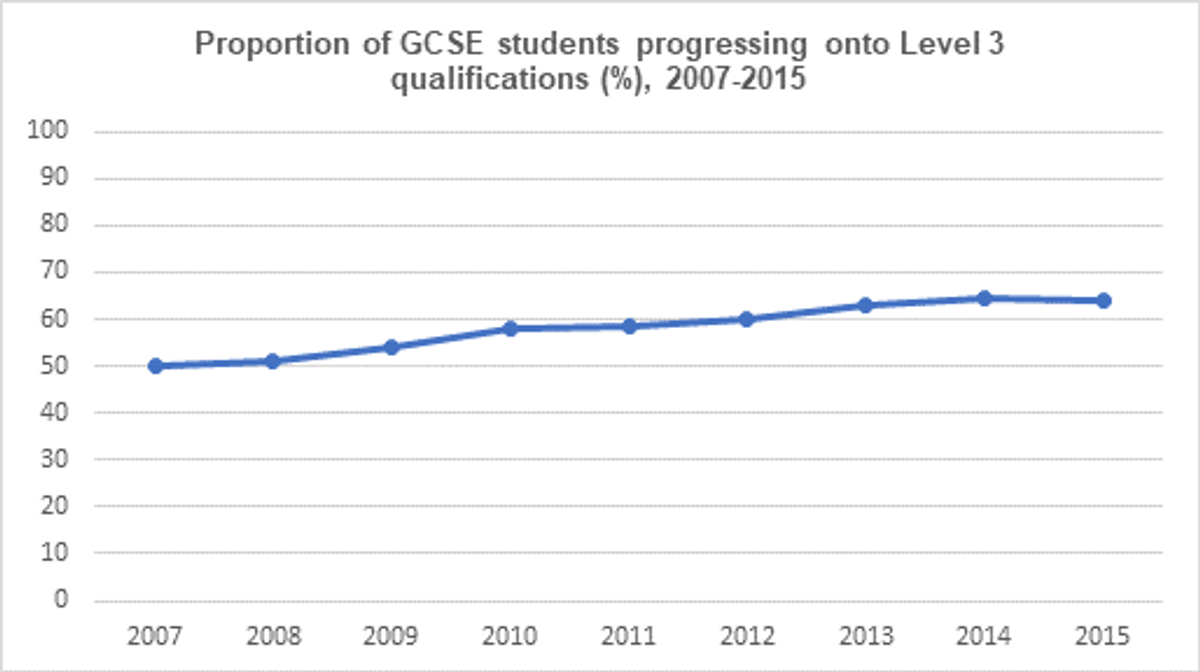

By increasing the proportion of GCSE students who enter for academic subjects, it may be expected that the number of students studying for Level 3 qualifications, and A-levels in particular, would increase in the years following the arrival of the EBacc.

The following chart shows that the proportion of Key Stage 4 students who progressed into approved academic, vocational and technical Level 3 qualifications increased moderately before and after the EBacc was launched.

Source: DfE, Statistics: 16-19 attainment & Statistics: GCSE (Key Stage 4) NB: Data from 2018 onwards was excluded from our analysis due to changes to DfE methodology in their A-Level and Level 3 qualification entries breakdown which meant the Level 3 qualifications excluded from school performance measures and had failed to meet specified course requirements were not counted in entries figures and would thus overestimate the proportion of Level 3 students studying A-Levels. Progression rate calculated using DfE methodology, dividing the total number of Level 3 students by the total number of Key Stage 4 pupils two years prior.

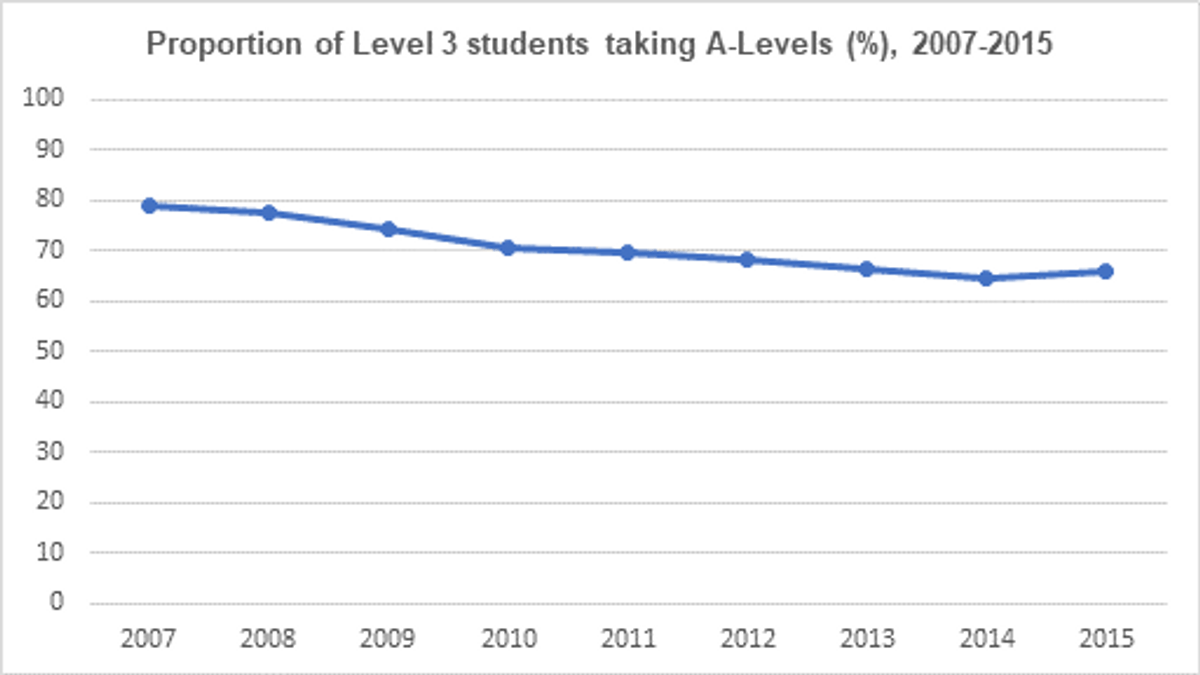

In relation to A-Levels specifically, the data suggests that that EBacc has not significantly affected the proportion of Level 3 students taking A-Levels. The negative trends pre-dates 2010 and the introduction of the EBacc:

Source: DfE, Statistics: 16-19 attainment

However, a more detailed insight of the EBacc’s effect on post-16 progression and the uptake of different Level 3 qualifications is restricted by data limitations and changes to methodology over the period of interest (2007-2021).

3.4. 16-18 progression pathways: A-Level choices

As the proportion of students entering for the majority of EBacc pillars has steadily grown over the last decade, it is reasonable to expect this would influence A-level subject choices.

Among post-16 students entering for A-Levels, has the introduction of the EBacc therefore been associated with changing patterns of subject choices during the last decade?

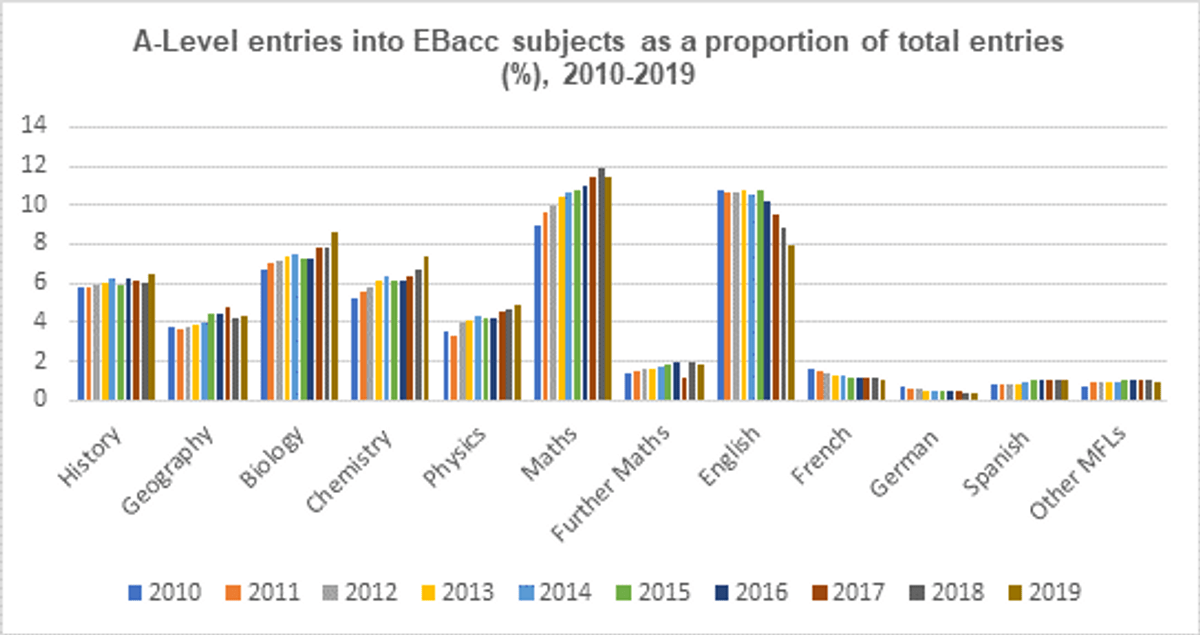

Between 2011 and 2019, the proportion of all A-Level entries to subjects in the EBacc rose by six percentage points from 50% to 56%.[28]

However, the growth in entries for EBacc subjects at A-Level has been unevenly spread, and largely driven by maths and the sciences, as the following chart shows:

Source: DfE, Statistics: 16-19 attainment. NB:Subjects included in the charts are based on the list of A-Level subjects from the government database covering the specified period, 2010-2019. The figure for English comprises entries for English Literature, English Language and English Language and Literature. This means that data on the percentage of entries into facilitating subjects is a slight overestimation, given that English Literature is the only English subject that formed part of the Russell Group’s facilitating subjects list. NB: Classical languages were excluded from the graph due to classical studies being accounted for in earlier releases, which includes entries for non-facilitating subjects (eg, Classical Civilisation).

Indeed, there has been a notable decline in English, French and German entries, and negligible changes in other subjects. It is also noteworthy that A-Level Language entries have been consistently low since 2010 despite at least two in five GCSE students entering for a language since 2014.

As such, it is difficult to draw reliable conclusions regarding the effect of the EBacc on A-Level entries to EBacc subjects, and to differentiate such effects from wider forces shaping student attitudes and choices when selecting their subjects at 17. For example, growing student interest in STEM subjects predates the EBacc.

| In a 2007 attitudinal survey investigating students’ perceptions of the relative importance of different subjects, both female and male students ranked maths, further maths and the individual sciences as highly important subjects to study. The value of STEM subjects was additionally recognised by low, middle and high-attainers. Subject selection was heavily tied to employment considerations by the vast majority of respondents (70%). Source: Rodeiro, C L. (2007) A Level Subject Choice in England: Patterns of Uptake and Factors Affecting Subject Preferences [Research Report]. Cambridge Assessment. pp. 28-30. |

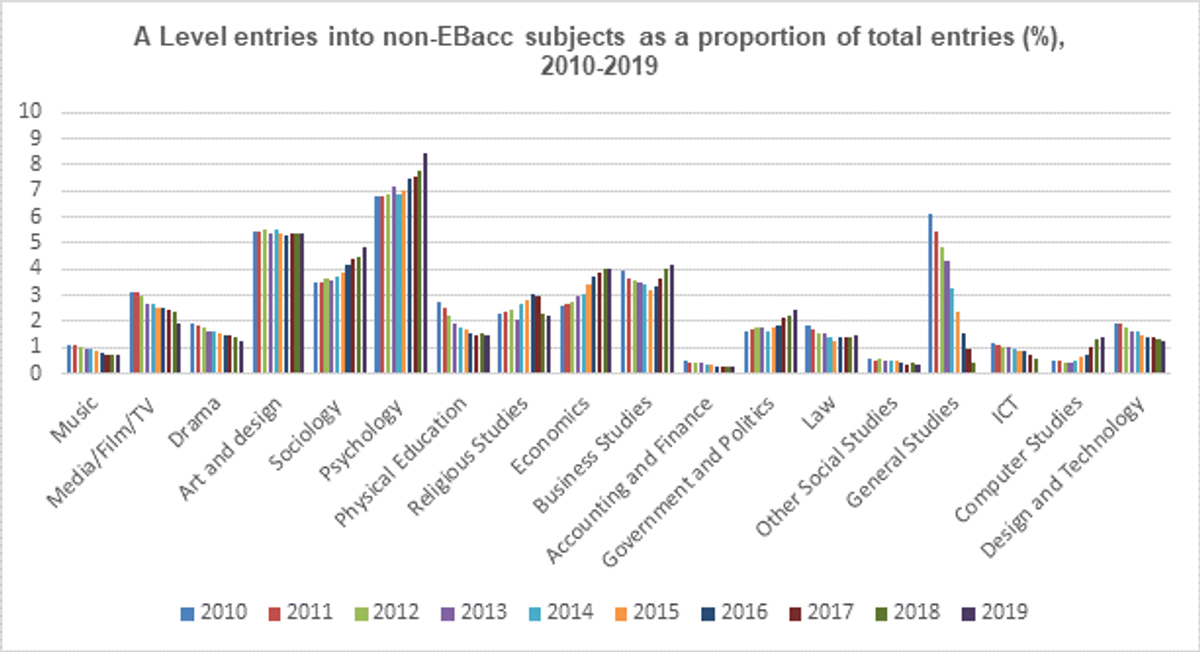

Turning to non-EBacc subjects at A-Level, entry data shows that over the last decade, while some subjects have seen declines – notably Drama and Music – other subjects have seen consistent entry growth, for example, Sociology and Psychology, as the following chart shows:

These entry patterns show that exclusion from the EBacc does not automatically mean particular subjects experience declines in corresponding A-level entries.

Overall, such evidence suggests that the effect of the EBacc on A-level entries has been limited:

- there appears to have been a modest increase in the proportion of students entering for A-levels and entering for EBacc subjects at A-Level

- however, while some EBacc subjects have seen a growth in A-Level entries to that subject over the last decade, some have declined, indicating the influence of other factors

- similarly, some non-EBacc subjects have seen a growth in entries at A-level over the last decade, despite their exclusion from the EBacc.

3.5. 16-18 subject choices and progression pathways: Higher Education

The government’s EBacc policy aims for more young people to enter for GCSE subjects that will keep their options open, in particular, the option of attending university.

Indeed, as noted above, a particularly strong motivating factor among Ministers has been ensuring that young people from socially-disadvantaged backgrounds are not excluded from attending the most selective and high‑status universities because of GCSE subject choices they made at age 14.

What changes in patterns of entry to Higher Education can be observed among students in England since the introduction of the EBacc in 2010?

Overall, the proportion of young people entering Higher Education has seen continuous growth since the introduction of the EBacc.

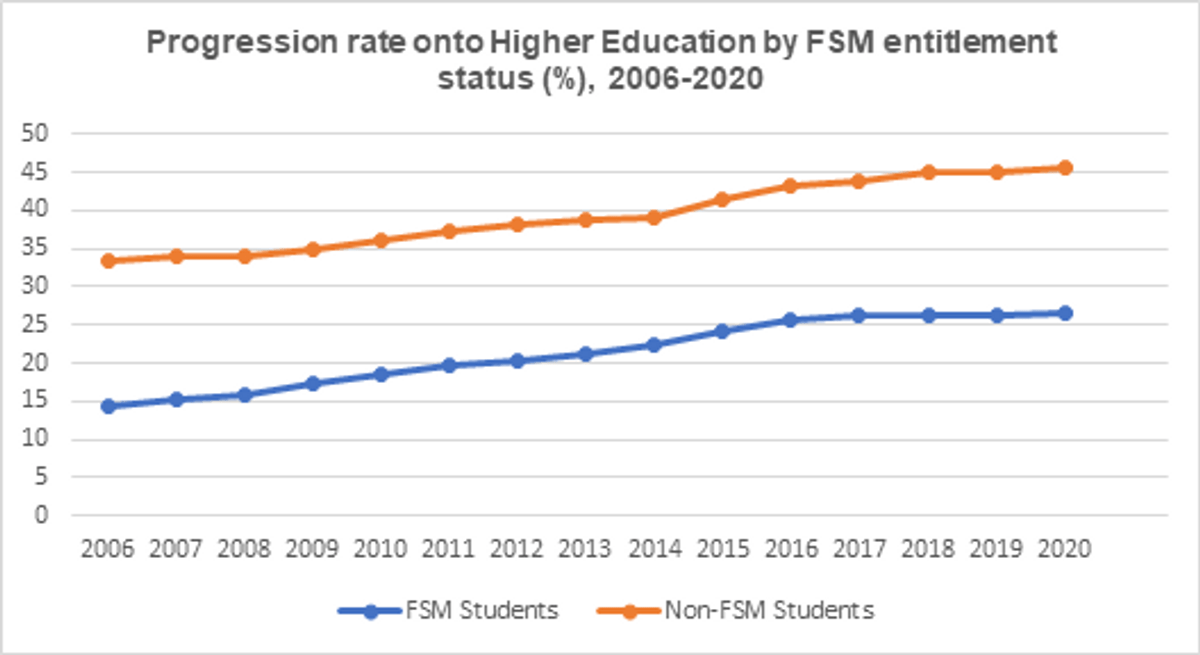

However, as the following chart shows, this trend predates the EBacc by a number of years, and differences remain for FSM students:

Source: Education Statistics Service.

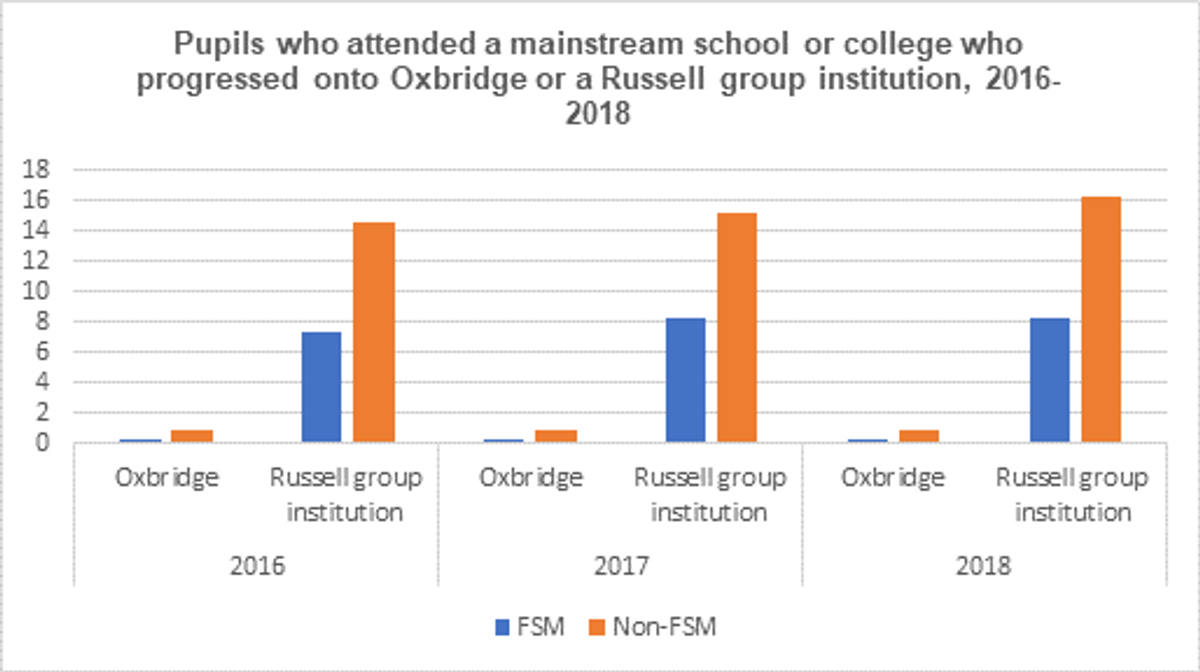

In relation to Russell Group and Oxbridge universities, recent data show negligible changes in the proportion of disadvantaged students going to these institutions.

Source: Education Statistics Service.

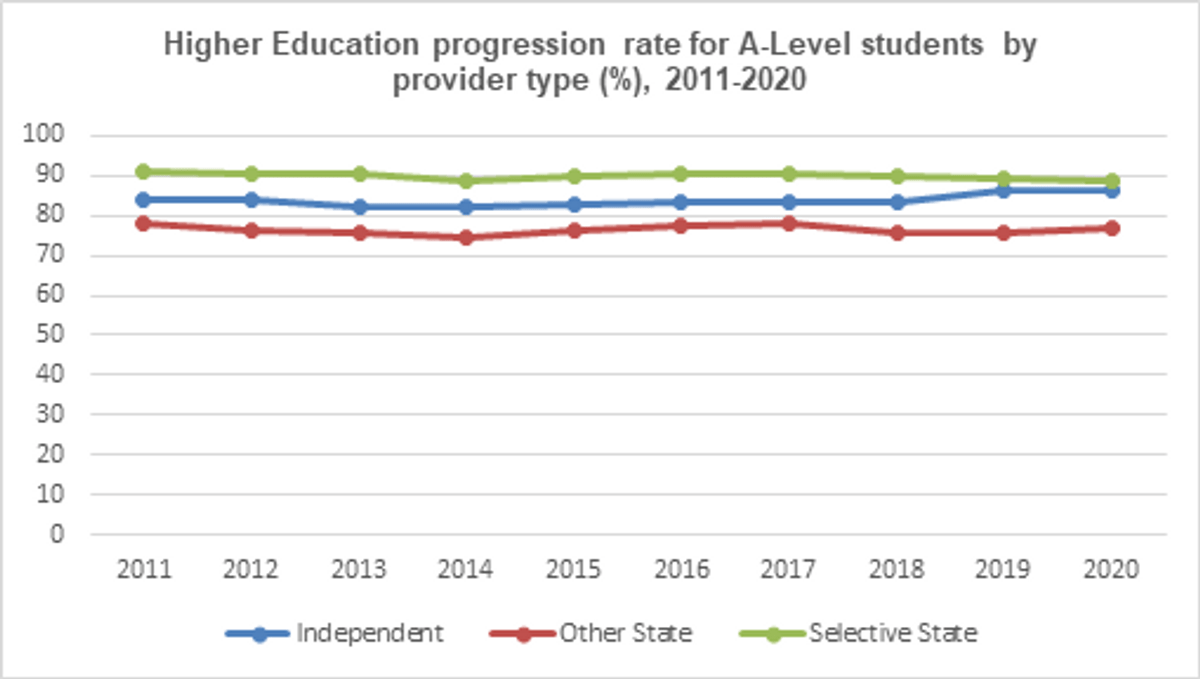

It is also notable that there has been little change in the proportion A-level students progressing to university since 2010 across different types of school, as the following chart shows:

Source: Education Statistics Service.

Has the introduction of the EBacc therefore resulted in more disadvantaged students attending (highly selective) universities? Overall, it is not possible to draw any reliable conclusions.

This is because multiple factors determine and shape HE participation decisions at an individual and cohort level. Since 2010, there have been many other policy interventions seeking to influence student decisions on attending university – wholly separate to the EBacc – with a particular focus on those from disadvantaged backgrounds. In particular, the ‘widening access’ agenda driven by universities and government has seen targeted interventions across the country, for example, mentoring disadvantaged students considering university.[29]

Indeed, the changes and complexity in the landscape of Higher Education admissions policy has meant that no research has been published showing a causal link between the introduction of the EBacc and university participation rates.

3.6. Conclusion: What has been the impact of the EBacc on student subject choices and progression?

The introduction of the EBacc has had significant influence on GCSE subject entry patterns. Were it not for specific issues related to GCSE language subjects, the government would likely have met its target for 75% of students to enter for the EBacc from a base of 20% in 2010.

However, the purpose of the EBacc is to keep young people’s post-16 options open for further study and future careers. Here, the impact of the EBacc is more ambiguous.

There has been some growth in the proportion of students progressing on to A-level studies and to A-levels in EBacc subjects – although multiple other factors may also be at work.

However, some EBacc subjects have seen a declining share of entries over the last decade and some non-EBacc subjects have seen steady growth.

There has been growth in the proportion of young people, including from disadvantaged backgrounds, attending university. However, this trend preceded the introduction of the EBacc and likely reflects a complex range of other factors, not least targeted government policy interventions to widen access, meaning it is not possible to discern a clear ‘EBacc effect’ on university entries.

4. Evaluating the EBacc

Key points:

- Is the EBacc the best stepping stone for progression to post-16 education and future careers?

- EBacc GCSEs do keep young people’s options open given - unlike many other Level 2 qualifications - they are accepted and used for entry to the widest range of Level 3 subjects and progression routes, including A-levels and vocational and technical qualifications. Some students are likely to make better choices and have better outcomes because of the EBacc.

- However, the EBacc may crowd out a more diverse curriculum and may close some options for students, eg creative arts. For some students, entering the EBacc may lead to lower levels of educational engagement and motivation, or lead to lower overall GCSE grades, thereby narrowing their options.

4.1. Introduction

The introduction of the EBacc into school performance measures in England over the last decade has had a clear effect on GCSE entry patterns.

While some stakeholders have welcomed these changes, others have criticised the EBacc and argued that it conflicts with other education policy goals, such as preparing young people for employment and can distort some of the other major barriers to post-16 progression.

This section therefore explores whether the EBacc is the best stepping stone for progression to post-16 education and future careers, what are the pros and cons of the EBacc and the trade-offs it imposes.

PROS:

4.2. The subjects in the EBacc keep young people’s options open

Although it is difficult to discern an ‘EBacc effect’ on post-16 choices and pathways, analysing the GCSE subjects included in the EBacc does suggest it fulfils the DfE’s aim of keeping young people’s options open.

This is because unlike many non-EBacc GCSEs and other Level 2 qualifications, EBacc GCSEs are accepted and used for entry to the widest range of Level 3 subjects and progression routes, including A-levels and vocational and technical qualifications (VTQ).

In contrast, for example, most Level 2 vocational and technical qualifications (VTQs) would not be accepted for admission to A-level courses in EBacc subjects in the absence of a GCSE in that subject.

Indeed, progression to A-level studies in most EBacc subjects - for example, in languages, maths or the sciences – is largely impossible without having first completed the corresponding GCSE.

On this basis, it is reasonable to conclude that the subjects in the EBacc do keep young people’s options open.

4.3. Some students make better choices and have better outcomes because of the EBacc

A key motivation for introducing the EBacc was to break the link between students’ socioeconomic backgrounds and their GCSE subject choices.

As set out above, the introduction of the EBacc has clearly had a significant effect on GCSE student choices, even if the effects on post-16 choices and pathways are more ambiguous.

Among those students whose GCSE subject choices have been influenced by the EBacc over the last decade, it is reasonable to assume that some have taken progression routes and options – such as attending high-tariff universities – which they would not have taken in the absence of the EBacc.

This group – who arguably represent the key ‘winners’ from the EBacc policy – are very difficult to estimate in terms of numbers or as a proportion of all students because it is impossible to know what path such students would have taken without the EBacc.

Nevertheless, the absence of detailed data on this group does not mean some students have not benefitted in this way from the introduction of the EBacc.

4.4. Improved overall attainment among some disadvantaged students

Some research has suggested that implementation of the EBacc policy has resulted in improved attainment among disadvantaged students, as schools responded to the EBacc and its accompanying performance measures by placing greater emphasis on performance in core subjects.

A study published in 2018 notes that for students entering their GCSEs between 2012 and 2014:[30]

Multilevel modelling revealed that taking the EBacc was associated with higher average GCSE scores. FSM students who entered the EBacc achieved average GCSE scores that were between two-fifths and half a grade higher than FSM students who studied a different subject combination. By contrast, the advantage gained by non-FSM students who studied the EBacc was between one-fifth and one-third of a grade. Since there is no obvious reason why any causal relationship between studying the EBacc and higher average GCSE scores would be stronger for FSM students, it seems likely that the association is linked to how schools resource the EBacc subjects and the traits of those students who are entered.

However, it should be noted that the improvements identified were small and only in average GCSE score not individual subject grades. Since it is the latter that is important for progression to the next stage of their education, it is not clear that any improvement in attainment have actually led to wider options and pathways for individual students.

4.5. A multidisciplinary curriculum can benefits students in later life

The EBacc encourages students to experience a broad and multi-disciplinary curriculum across its five ‘pillars’ until the end of Key Stage 4. There is evidence to suggest that a broad multidisciplinary curriculum yields benefits to students.

For example, although not proving a causal relationship, a 2021 report from the Education Policy Institute highlighted the limitations to a narrower education by studying the earnings of those students who had restricted their studies at 16-19. When comparing two students who had taken subjects across one or two subject groups, individuals who had studied a broader curriculum typically earned 3-4% more, and earning differences by age 26 were comparable to factors such as higher education institution attended and socioeconomic status.[31]

It has also been argued that a broad curriculum promotes rounded and balanced individuals who possess a stronger skill-set to confront different types of workplace challenges. For example, a trial studying the performance of junior doctors indicated that an enjoyment of humanities subjects fostered healthy and balanced attitudes that maximised job performance.[32]

CONS:

4.6. The EBacc may crowd out a more diverse curriculum and may close some options for students

The EBacc does not limit the number or type of qualifications that students can enter for at Key Stage 4. However, in practice, most students enter for around eight GCSEs,[33] so have limited scope to enter for non-EBacc GCSEs.

As such, the EBacc’s focus on core, academic subjects arguably narrows young people’s experience of the curriculum by crowding out other opportunities and experiences. These include non-EBacc GCSEs in the creative arts, but also vocational and technical qualifications, as well Higher Project Qualifications.

In addition, while the subjects in the EBacc do keep young people’s options open, some doors may be closed for students. In particular, the exclusion of some creative arts subjects from the EBacc may prevent some students from entering them at A-level or pursuing further study and careers in them.

The withdrawal of the Russell Group’s facilitating subject A-Level guidance in 2019 has also raised questions around the choice of subjects in the EBacc, particularly given the EBacc’s aim of enhancing the prospects of disadvantaged students from attending highly selective universities.[34]

4.7. Some students may have a poor educational experience because of the EBacc

Despite the breadth of academic subjects it comprises, some students may very have little interest in EBacc GCSE subjects.

For example, a survey of around 4,000 state-funded secondary school teachers undertaken for this report asked respondents to what extent they agreed with the statement:

For some students, subjects outside the EBacc are more likely to engage them with their GCSE studies

Three quarters of respondents agreed with this statement, and only 1% disagreed:

| Strongly agree | 35% |

| Agree | 40% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 11% |

| Disagree | 1% |

| Strongly disagree | 0% |

| Not relevant/cannot answer | 12% |

Low levels of interest in their EBacc GCSE studies may also result in lower levels of enjoyment, motivation and educational engagement, and overall, lead to a poor educational experience if pupils are deprived of the opportunity to study subjects they are passionate about. This could in turn have knock-on consequences for a student’s Level 3 studies.

Detailed evidence of the effects of entering for the EBacc on student motivation and engagement among different types of students is not available. However, risks around the EBacc in this regard are noteworthy given the availability of evidence that attainment is linked to subject enjoyment and engagement.[35]

4.8. Some students may achieve lower average GCSE grades because of entering for the EBacc, thereby narrowing their options

The purpose of the EBacc is to ensure that young people are not held back by the subjects they chose to study at GCSE. However, the progression options facing students are also determined by the grades they achieve. The purpose of the EBacc is therefore undermined if young people achieve lower grades as a result of entering for the EBacc, closing doors to their progression.

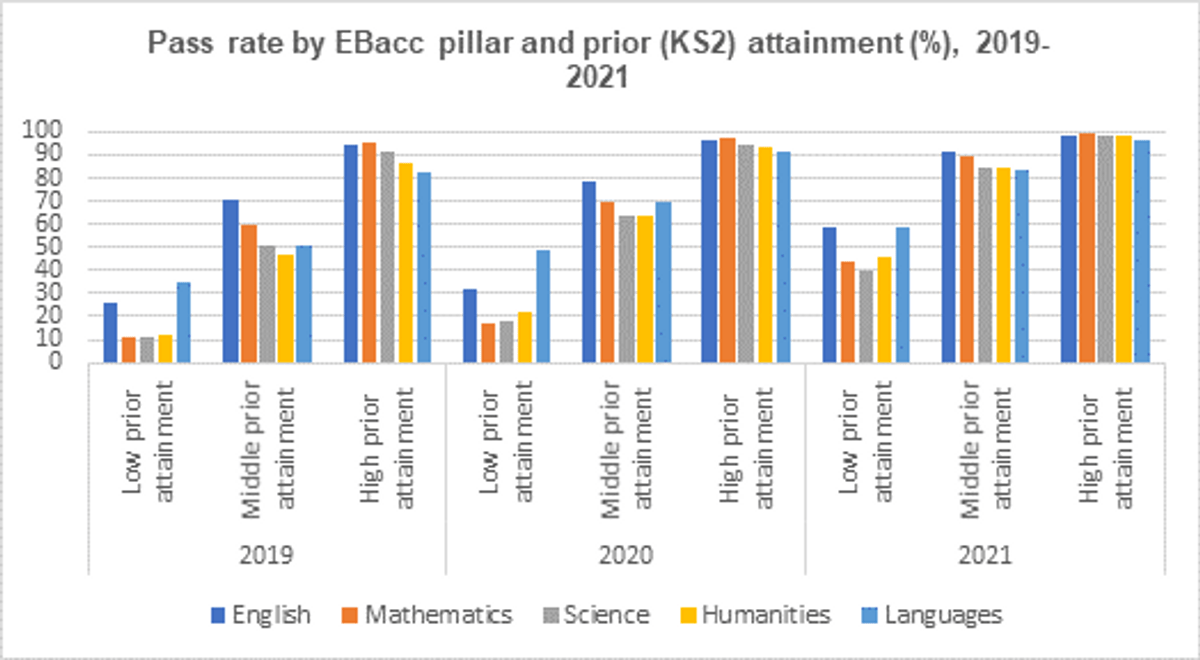

Attainment data clearly shows that students with lower prior attainment (Key Stage 2 score) are less likely to achieve a grade 4 or above in some EBacc pillars than others, as the following chart shows:

Source:Education Statistics Service.

This raises the question of whether some students would achieve higher overall grades – and have wider post-16 options – if they entered for more non-EBacc subjects. For example, some students may achieve higher overall grades if they had more opportunity to select GCSE subjects they are interested in.

Worryingly, there is some evidence that certain types of students may achieve lower grades overall by entering for the EBacc. A 2020 study found that FSM pupils in the same prior attainment bracket as their non-FSM peers were more likely to fail multiple EBacc subjects.[36] Indeed, the study found that, between 2010 and 2014, the percentage of pupils who entered but did not achieve the EBacc grew from 50% to 57% for FSM students, but 28% to 37% for non-FSM pupils.

Therefore, the is an opportunity cost to be mindful of in consideration to the policy objective striving for the vast majority of students to study an EBacc curriculum. Whilst some students will and have observed high-attainment in EBacc subjects, the ones who fail the EBacc may have reduced prospects for Level 3 study.

4.9. Limited direct preparation for non-academic post-16 options

Just under half of GCSE students do not enter academic post-16 pathways.

While the academic content covered in EBacc GCSEs may provide a strong basis for studying post-16 vocational and technical qualifications, it provides limited direct preparation, for example, experience of non-academic subject content.

4.10. Pressure on the provision and health of non-EBacc subjects

Since the introduction of the EBacc, entries for non-EBacc GCSE subjects in England have declined.

For example, groups such as the Cultural Alliance have argued that the implementation of the measure has partly contributed to a 27% drop in GCSE arts subjects 2010-2017 due to schools’ encouraging their students to take additional EBacc subjects.[37]

As noted in the previous section, entries for a number of non-EBacc A-level subjects have grown since its introduction, suggesting that exclusion from EBacc does not automatically force subjects into decline.

Nevertheless, where non-EBacc subjects have experienced declining entries, this may result in centres withdrawing them from the curriculum and, more generally, may put pressure on provision, the sustainability of employing specialist teachers, etc.

Some stakeholders have also raised concerns that the EBacc encourages a ‘two-tier’ attitude toward subjects and qualifications by delineating ‘high-status’ EBacc GCSEs. It has also been argued that the choice of subjects in the EBacc represents ‘class bias’, i.e. subjects more closely associated with affluent groups – such as foreign languages and history – approved as ‘superior’ subjects by the government.[38]

4.11. Conclusion

Is the EBacc the best stepping stone for progression to post-16 education and future careers?

As a curriculum policy, the EBacc prioritises keeping young people’s options open, in particular the option of entering high-status universities or careers. Since its introduction, some individual students will have benefitted from being directed toward the EBacc, and the breaking of the link between Key Stage 4 subject choices and socioeconomic background.

However, the focus on the goal of keeping young people’s options open is associated with trade-offs, for example, in relation to the educational experience of students with lower levels of interest in EBacc GCSEs, as well as students who may achieve lower overall GCSE grades as a result of entering for the EBacc.

In short, there are both pros and cons to the EBacc as a stepping to post-16 education and training.

This is reflected in the views of around 4,000 secondary school teachers who were surveyed for the purposes of this report.

The findings revealed that teachers are split three ways between supporting, opposing and being ambivalent toward key tenets of the EBacc policy.

Respondents held mixed views regarding whether the EBacc keeps a young person’s post-16 options open:

Entering for all the GCSE EBacc subjects keeps a young person's post-16 options more open than not completing the EBacc

| Strongly agree | 4% |

| Agree | 25% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 30% |

| Disagree | 21% |

| Strongly disagree | 8% |

| Not relevant/ cannot answer | 12% |

"Encouraging all types of students to enter for the full EBacc suite of subjects is good for social mobility

| Strongly agree | 4% |

| Agree | 25% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 29% |

| Disagree | 23% |

| Strongly disagree | 8% |

| Not relevant/ cannot answer | 12% |

"Entering for the full EBacc suite of subjects is good for students even if they do not go on to A-levels or University

| Strongly agree | 3% |

| Agree | 26% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 30% |

| Disagree | 22% |

| Strongly disagree | 8% |

| Not relevant/ cannot answer | 12% |

The GCSEs that currently comprise the EBacc represent the right suite of subjects and should not be changed

| Strongly agree | 3% |

| Agree | 19% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 30% |

| Disagree | 23% |

| Strongly disagree | 10% |

| Not relevant/ cannot answer | 15% |

These findings indicate that a substantial proportion of secondary school teachers retain doubts or scepticism regarding the EBacc. However, overall, secondary school teachers are not against the EBacc.

Given such mixed views among teachers, would it be possible to keep young people’s options open while addressing some of the disadvantages associated with the EBacc? Options for policymakers are explored in the next chapter.

5. A Different Stepping Stone? EBacc options for policymakers

Key points:

- Would a different EBacc provide a better stepping stone to post-16 education and careers? Policymakers have several options, each with different pros and cons.

- These include widening the EBacc to give students greater choices and flexibility, or introducing multiple EBacc suites geared toward technical subjects, science subjects, etc. in order to allow students to choose a route more aligned to their interests aged 14. Policymakers could also remove the EBacc from school performance measures and instead use information and advice to guide GCSE subject choices.

5.1. Introduction

Would a new, different EBacc provide young people with a better stepping stone to post-16 progression and student choices? Given the trade-offs of the EBacc identified above, could changes to the EBacc retain its benefits while addressing some of its challenges?

This section considers the EBacc options for policymakers.

5.2. Narrow the EBacc

Summary: Narrow the breadth of the EBacc for students by either reducing the number of GCSE subjects students must enter for, or dropping one or more ‘pillars’.

Description: To enter the EBacc, students must take up to eight GCSEs across five subject ‘pillars’. The number of GCSEs students have to enter for could be reduced while retaining compulsory subjects (English and maths). Alternatively, instead of five academic pillars – English, Mathematics, Science, Humanities and Languages – the number of academic pillars could be reduced by making the humanities or language pillars optional.

Pros:

- Greater opportunity for students to enter for non-EBacc subjects, potentially improving their motivation, engagement and interest in their studies.

- Increased scope for students to enter for fewer GCSEs enabling them to engage in more extra-curricular activities, applied learning, studying for vocational qualifications or soft-skills.

Cons:

- Increased scope for family, socioeconomic and other influences on student decision-making, potentially strengthening the link between student background and subject choices.

- May narrow student options post-16, eg students unable to enter for a language A-level having not studied a GCSE language.

Given most students won’t enter the labour market for a further two to five years, their long-term outcomes may be enhanced by focusing on academic subjects at 14-16 and using post-16 education to focus on applied learning, soft skills, etc.

5.3. Widen the EBacc to include more GCSE subjects

Summary: Increase the number of pillars and subjects in the EBacc.

Description: In order to give students more choice and flexibility, while nevertheless guiding them to subjects that will keep their options open and limit the influence of background on their choices, additional GCSE subjects could be introduced into the EBacc. These could form the basis of new academic ‘pillars’, such as the latter three in the table below. In order to manage student workload, entry requirements across the EBacc pillars could be recalibrated.

| English | English Literature and English Language |

| Maths | Foundation or Higher |

| Science | Combined or Triple, Computer Science (optional) |

| Humanities | History or Geography |

| Languages | French, Spanish, German, (Mandarin) Chinese, Biblical Hebrew, Persian, Turkish, Portugese, Classical Greek, Latin, Japanese, Urdu, Russian, Dutch |

| Creative arts | Art, Design and Technology (D&T), Dance |

| Applied GCSEs | Business Studies, Electronics, Engineering, Economics |

| Social sciences | Sociology, Psychology, Religious Studies |

Pros:

- Greater opportunity for students to enter for non-EBacc subjects which may interest them more, potentially improving their motivation, engagement and attainment.

- Improves the status and health of non-EBacc subjects, and addresses demands for a more inclusive curriculum.

Cons:

- Some student choices may narrow their post-16 options.

- Provision of non-EBacc subjects varies across centres, such that not all students may have the opportunity to benefit from greater choice.

5.4. Widen the EBacc to include VTQs and HPQs

Summary: Include selected non-GCSE Level 2 qualifications, such as recognised vocational and technical qualifications (VTQs) and Higher Project Qualifications as options in the EBacc.

Description: In addition to the existing five ‘pillars’ in the EBacc, additional pillars are introduced, focused on broadening the curriculum through access to a wider range of qualifications, ie non-academic vocational and technical qualifications, as well as Higher Project Qualifications. In order not to disadvantage students interested in taking a vocational or technical qualification, all students could be required to enter for at least one qualification per pillar.

| English | English Literature and English Language |

| Maths | Foundation or Higher |

| Science | Double or Triple, Computer Science (optional) |

| Humanities | History or Geography |

| Languages | French, Spanish, German, (Mandarin) Chinese, Biblical Hebrew, Persian, Turkish, Portugese, Classical Greek, Latin, Japanese, Urdu, Russian, Dutch |

| Applied subjects' pillar | Preparation for Life and Work; Health, Public Services and Care; Arts, Media and Publishing; Business Administration and Law; Leisure Travel and Tourism; Construction, Planning and Built Environment; Retail and Commercial Enterprise; Engineering and Manufacturing Technologies; Information and Communication Technology; Education and Training; Agriculture, Horticulture and Animal Care Higher Project Qualification |

Pros:

- Greater opportunity for students to enter for non-EBacc subjects which may interest them more, potentially improving their motivation, engagement and attainment.

- Increases opportunities to acquire wider skills (including soft skills) and experience.

- Improves currency of higher-value non-GCSEs, such as Higher Project Qualifications and tackles the perception of ‘second-rate qualifications’.

- Taking a VTQ at Key Stage 4 may provide for a better transition to studying VTQs post-16 for those students who take this pathway, for example, providing more information on what it is like to study VTQs.

Cons:

- Provision of non-academic qualifications varies across schools and many students may simply not be able to access them.

5.5. Introduce a 'flexible pillar' choice to the EBacc

Summary: Include a ‘flexible choice’ EBacc pillar that can be any single, approved academic or vocational, technical qualification.

Description: In addition to the existing five pillars of the EBacc, an additional ‘flexible choice’ pillar is introduced, which can be any approved GCSE, VTQ or HPQ.

Pros:

- Ensures that – notwithstanding limitations on provision among schools – every student can enter for a qualification at Key Stage 4 that they are passionate about.

- Greater choice and flexibility for students, including greater scope for students to enter a subject they are most interested in, potentially improving their motivation and engagement.

Cons:

- Provision of non-GCSE qualifications among schools is variable

- Inequalities within cohorts may widen if some students use their ‘flexible choice’ to enter for additional EBacc subjects.

5.6. Introduce multiple EBacc suites

Summary: Introduce multiple different EBacc routes – a Technical EBacc, Science EBacc, Arts EBacc - to support multiple routes to entering for high-quality GCSEs.

Description: Rather than a single EBacc suite, multiple EBacc suites are introduced covering core subjects, but geared toward allowing students to focus on science, creative arts, technical qualifications, etc. – thereby allowing students to choose a route more aligned to their interests.

Pros:

- Recognises that students’ have different interests but limits the influence of background on subject choices by providing an ‘approved’ suite of subjects.

- Increased opportunity for students to enter for subjects that interest them more, potentially improving their motivation, engagement and attainment.

Cons:

- Requires students to specialise in a specific pathway at an earlier age, narrowing their post-16 options, and hindering those students whose interests evolve during their Key Stage 4 studies, eg from the arts to the sciences.

5.7. Use information and advice, rather than school performance measures, to guide subject choices

Summary: Remove the EBacc from school performance measures and introduce a new, enhanced information, advice and guidance framework to shape student GCSE choices.

Description: Schools are no longer subject to the performance measures based on the EBacc. Instead, enhanced information, advice and guidance for students and parents is used to promote awareness of the options that different EBacc GCSE subjects keep open, and the value of choosing a broad and balanced curriculum at GCSE. Maths and English and sciences remain compulsory.

Pros:

- Increased opportunity for students to enter for subjects that interest them more, potentially improving their motivation, engagement and attainment.

Cons:

- In the absence of the EBacc – and despite the availability of information, advice and guidance – the influence of social, family and other factors on student GCSE choices would grow, potentially resulting in some students not joining higher-status universities or careers, undermining social mobility.

5.8. Conclusion

The EBacc could be reconfigured in various way to provide a different – and potentially improved - stepping stone to post-16 education and training that keeps young people’s options open.

However, each option presents different pros and cons. In particular, while increased flexibility around subject choices may improve outcomes for some students, it comes at the risk of post-16 options being narrowed by choices at age 14, and greater influence of socioeconomic and other factors on these choices.

6. Conclusion

Key points:

- Students would be best served if debate on the EBacc focused on whether it provides the best stepping stone to post-16 education and training relative to other options.

- While the choice of subjects in the EBacc does keep young people’s options open, there is insufficient evidence to say whether the EBacc policy overall has achieved this aim, has done so equitably for all types of student, and whether the trade-offs involved are justified.

- More research is required, for example, into relative levels of motivation, enjoyment and education at the end of Key Stage 4 among different students who enter for three, four and five EBacc pillars, and different subject combinations.

6.1. Introduction

Like any curriculum policy, debate on the EBacc has sometimes been dramatised in regards to what knowledge and skills society values and how this relates to the subjects pupils are encouraged to study under the current school performance framework.

However, students would be better served if debate focused on whether the EBacc provides the best stepping stone to post-16 education and training relative to other options, such as widening the EBacc to include other GCSEs or non-academic qualifications.

Judging between different options requires careful consideration and evaluation, for example, the extent to which widening the EBacc might improve levels of student interest, engagement and motivation, but risk students narrowing their post-16 options as a result.

This is something that can be studied across multiple dimensions for different types of students.

However, such evidence is simply not available currently despite the data generated by hundreds of thousands of students taking GCSEs each year and the wide variety of GCSE pathways that students still pursue.

In short, a gigantic gap in evidence on the EBacc is preventing the kind of informed debate that students deserve.

Indeed, whilst the choice of students in the EBacc does keep young people's options open, there is insufficient evidence to say whether the EBacc policy has done so equitably for all types of students, and whether the trade-offs that related to streamlining students into a specific suite of subjects is justified.

In conclusion, a number of recommendations for policymakers can be made:

6.2. Undertake more research into the experience, options and progression of different types of students who enter for the EBacc

A major programme of research is required to be able to fully evaluate the trade-offs currently posed by the EBacc’s focus on keeping young people’s options open. For example, research is urgently needed to investigate:

- The impact of entering for three, four and five pillars of the EBacc on overall GCSE grades among different types of student.

- The longitudinal impact of entering for the full EBacc on students’ post-16 options at A-Level, Higher Education and the jobs that they enter.

- The extent to which schools prioritise full EBacc provision with provision of non-EBacc subjects.

- Short and long-term benefits to students of different kinds of multidisciplinary curriculula.

- Whether the introduction of the EBacc has influenced Level 3 vocational and technical qualification choices.

6.3. Use progression data to inform the design of the EBacc

At its launch, the choice of subjects in the EBacc was based upon the Russell Group’s list of ‘facilitating subjects’.

However, since then, the data available on GCSEs and young people’s pathways has been transformed.

In future, various types of data could be used by policymakers to understand how effective the choice of subjects in the EBacc is in keeping a young person’s options open.

For example, student-level pathways could be analysed to identify which GCSE subject combination is associated with the most diverse progression pathways.

Alternatively, the entry requirements for Level 3 and higher education institutions could be surveyed in order to identify which subjects are required for the widest range of courses.

Adopting such a data-driven approach to setting the EBacc subjects would reassure stakeholders and build trust in the EBacc policy.

[1] Woolcock N (2022) Pupils should learn the world’s rich history, says schools minister, The Times.

[2] Department for Education (2014) GCSE subject content [Collection].

[3] DfE (2019) English Baccalaureate (EBacc) [Guidance].

[4] DfE (2021) English Baccalaureate: eligible qualifications[Guidance].

[5] Ofqual (2021) Analysis of results: A levels and GCSEs, summer 2021[Research and analysis].

[6] Department for Education (2020) Secondary accountability measure: Guide for maintained secondary schools, academies and free schools [Guidance].

[7] DfE (2019) English Baccalaureate (EBacc) [Guidance].

[8] Wenchao, J., Muriel, A. & Sibieta, L. (2010) Subject and course choices at age 14 and 16 amongst young people in England: insights from behavioural economics [Research Report] Department for Education. pp. 37-40.

[9] DfE (2012) The effects of the English Baccalaureate [Research Report].pp. 17-18.

[10] Henderson, M., Sullivan, A., Anders, J., & Moulton, V. (2018). Social class, gender and ethnic differences in subjects taken at age 14. The Curriculum Journal, 29(3), 298-318.

[11] Henderson, M., Sullivan, A., Anders, J., & Moulton, V. (2018). Social class, gender and ethnic differences in subjects taken at age 14. The Curriculum Journal, 29(3), p. 309.

[12] Sullivan, A., Zimdars, A., & Heath, A. (2010). The social structure of the 14–16 curriculum in England. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 20(1), p. 18.

[13] DfE (2017) Implementing the English Baccalaureate [Government consultation response] p.5.

[14] Hansard (2019, March 21) Education- Childcare Settings: Financial Viability.

[15] Social Market Foundation (2021, July 22) Rt Hon Nick Gibb MP, Minister for School Standards, delivers speech on knowledge-rich curriculum to the Social Market Foundation [Transcript].

[16] DfE & The Rt Hon Nick Gibb MP. (2011, June 7). Nick Gibb to the 2011 HMC Deputy Heads Conference [Transcript]

[17] The Russell Group (2022) Informed Choices [Online].

[18] Anders, J. et al (2017) Incentivising specific combinations of subjects: does it make any difference to university access?, Centre for Longitudinal Studies, pp. 9, 24-27.

[19] Britton, J. et al (2020) The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earningsDfE &Institute for Fiscal Studies [Research report] pp. 40-41

[20] Hodge, L. et al (2021) GCSE attainment and lifetime earnings. Government Social Research [Research Report] p. 14.

[21] Hodge, L. et al (2021) GCSE attainment and lifetime earnings. Government Social Research [Research Report] P. 32.

[22] See DfE & The Rt Hon Nick Gibb MP (2017, October 19) Nick Gibb: The importance of a knowledge-based education [Transcript]; Nick Gibb (2017) Nick Gibb: the importance of education research. Public Sector Network.; Robin Walker MP (2021, October 28) Black History Month [Hansard].; Social Market Foundation (2013, 5 February) Michael Gove speaks at the Social Market Foundation [Transcript].

[23] Hirsch Jr, E. D. (2011). Beyond Comprehension: We Have yet to Adopt a Common Core Curriculum that Builds Knowledge Grade by Grade--But We Need to. American Educator, 34(4), pp.30-36.

[24] DfE (2021) Statistics: GCSEs (key stage 4) [Collection].

[25] Ofqual. (2021). Provisional entries for GCSE, AS and A Level: summer 2021 exam series [Official Statistics].

[26] L. Hagger-Vaughan. (2020). Is the English Baccalaureate (EBacc) helping participation in language learning in secondary schools in England?. The Language Learning Journal, 48(5),p.523.

[27] Long, E. & Danechi, S. (2019). English Baccalaureate [House of Commons Briefing Paper] p. 22.

[28] DfE A level and other level 3 results: [2011-2019].

[29] Robinson, D. & Salvestrini, V. (2020) The impact of interventions for widenining access to higher education: a review of the evidence[Report] p.10.

[30] Armitage, E. & Lau, C. (2020) Can the English Baccalaureate act as an educational equaliser?, Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 27:1

[31] EPI (2021) A narrowing path to success? 16-19 curriculum breadth and employment outcomes[Report]. p. 8.

[32] Mangione, S. et al. (2018) Medical Students' Exposure to the Humanities Correlates with Positive Personal Qualities and Reduced Burnout: A Multi-Institutional U.S. Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33(5):628-634.

[33] Ofqual (2021) Summer 2021 results analysis and quality assurance- A level and GCSE [Research and analysis].

[34] Richmond, T. (2019)A step Baccward: Analysing the impact of the ‘English Baccalaureate’ performance measure[Report] p.3.

[35] Flynn, D. (2014). Baccalaureate attainment of college students at 4-year institutions as a function of student engagement behaviors: Social and academic student engagement behaviors matter.

[36] Armitage, E. & Lau, C. (2020) Can the English baccalaureate act as an education equaliser?, Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 27(1), Pp. 116-118.

[37] Cultural Learning Alliance (2017, July 20). Trends in arts subjects.

[38] Burgess, A., & Burgess, L. (2020). “Social class and Art & Design education: A significant omission” in Debates in Art and Design Education, Routledge: 2020, pp. 156-182.